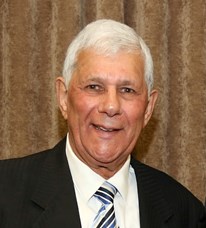

Dr Robert Isaacs AM, OAM - Aboriginal Elder

Please note Dr Isaacs works externally to the Commissioner's office.

Please note Dr Isaacs works externally to the Commissioner's office.

My name is Dr. Robert Isaacs AM, OAM, JP, PhD and I am an Aboriginal Elder from the Whadjuk-Bibilmum Wardandi Noongar language group. I am a member of the Stolen Generation. I was raised as a ward of the state under the Native Welfare Department.

I grew up in institutions including St Joseph’s Orphanage, Castledare Boys Home, and finally Clontarf Boys Town. I left at the age of 17 with nothing but a battered suitcase and the shirt on my back, and went to work at Aherns department store before joining the Army Reserves.

I was unaware of my Aboriginal heritage until I began my career with the Community and Child Health Service Department in 1973. Through my work I met a member of my clan, and that chance meeting led to a discovery that shaped the rest of my life.

My passion is finding ways to work with the government and the community to support Aboriginal and other disadvantaged groups – and ensure their access to health, housing and education. Today, I lead Keystart’s Social Lending Scheme and Chair the Aboriginal Lands Trust.

I was raised in orphanages and educated at Clontarf Boys Town, I had no family, no tender love and care, but I was given something very valuable - an education. That education has allowed me to travel a long and challenging journey since leaving the gates of Clontarf.

It has given me the confidence and grounding I needed to go on to lead initiatives in social justice, health, education, housing, employment and Aboriginal affairs.

When I spent the holidays with a kindly foster family, I saw the love, care and effort that went into a family. I saw how working hard ensured there was always food on the table, a roof over their heads, nice cars and clothes and plenty of love to go around. I wanted that for myself, for my future.

I began my working life in an era influenced by a lack of cultural awareness about how best to work with and support Aboriginal communities; no knowledge whatsoever about the specific health needs of Aboriginal people and a deep sense of mistrust between Aboriginal people and white Australian health care providers.

I am proud to say that a great deal has changed – for the better – in my lifetime. I joined the public service as a health worker in the 1970’s after being inspired by my now wife Teresa, an Aboriginal nurse, to help others.

Through our work, I saw how Aboriginal people struggled to communicate with health providers, that people didn’t know what services were available to them or how to access appropriate services.

I saw how Aboriginal people were disconnected from white Australian society and their lands and how struggling with having a home, education or a job affected people’s sense of identity and ability to deal with the basics like good food and hygiene. There were times when the challenges seemed insurmountable. I just broke down the issues into manageable sections, put my head down and tried to come up with one solution at a time.

Through my studies at Curtin University I was selected to go to Salt Lake City USA on a Rotary Exchange Program. There I learnt about Indigenous health, housing and education programs and it’s where I got my first real taste of practical, self-determining programs that really worked to improve the everyday lives of Indigenous people. I saw how Indigenous communities were starting to develop and run their own health initiatives.

I realised that it didn’t matter how much funding the government provides - these programs only work when the funding is used by Aboriginal people, for Aboriginal people. Aboriginal people need to own the process and the outcomes.

As my career progressed I became involved in Aboriginal housing and government affairs. I realised that everything was interconnected – without safe and secure housing, Aboriginal people lacked the basic environment for good health.

A home provides the stability youth need to go to school and gain an education. It’s important to recognise that Aboriginal people are disadvantaged, in many cases, by ongoing discrimination, poverty, cultural differences and broken homes. Aboriginal people suffer from decades of resentment and racism that has damaged family relations, resulted in substance abuse and caused mental health issues. But moving forward, Aboriginal people need to take charge of our own health, improve our wellbeing and give our children the best possible start in life.

Together, we can help our people take control our destiny. The problems of the past can no longer be a determinant of our future. The key to breaking the cycle is education. Not just for young people but also their parents, if we could truly engage parents, we’d have a real head start in closing the gap and putting the trauma and disadvantage of earlier generations behind us.

I want to see our youth and our people take pride in themselves; not just for what we were, as the first people of this country, but also what we can be - self-determining and in charge of our own destinies.