Supportive relationships

All young people have the right to be loved and to feel safe and supported by positive and healthy relationships. Young people who are supported by safe and positive relationships are more likely to have good mental health, be resilient, able to learn and sustain healthy relationships into the future.

Young people aged 12 to 17 years are experiencing the various physical, cognitive and emotional changes associated with adolescence. Positive relationships with family, friends and other adults are critical to provide support during this period.

Last updated August 2020

Some data is available on whether WA young people aged 12 to 17 years are supported by safe and healthy relationships.

Overview

This indicator reports on a number of key measures that aim to track whether young people in WA have supportive relationships including relationships with parents, friends and other adults.

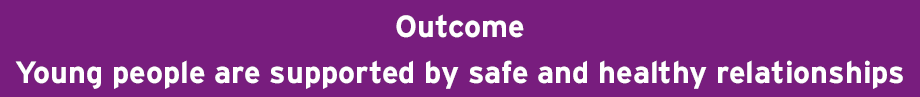

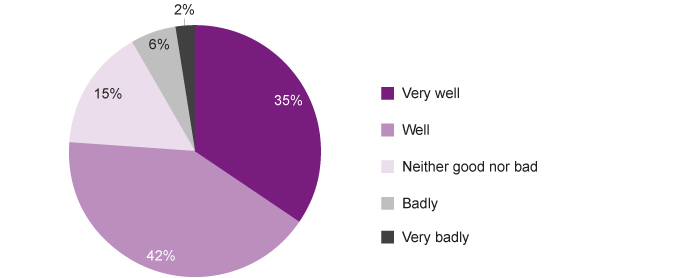

Over three-quarters (76.4%) of Year 7 to Year 12 students report that their family gets along very well or well.

Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 students reporting that their family gets along very well, well, neither good nor bad, badly or very badly, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

The majority (85.2%) of students in Year 7 to Year 12 feel they have enough friends.

Areas of concern

Fewer Year 7 to Year 12 students feel their dad cares a lot about them compared to their mum (70.0% compared to 82.5%). Among female students, only 66.7 per cent feel their dad cares about them a lot and only 44.0 per cent feel that it is very much true that there is a parent or another adult they can talk to about their problems.

There is limited information available on whether WA young people in care are supported by healthy and positive relationships.

Only 60.9 per cent of young people with disability felt that they dad cared about them a lot and 80.5 per cent felt their mum cared about them a lot.

Last updated August 2020

All young people have the right to live with a family who cares for them and keeps them safe. As children enter their teenage years the relationships with their friends and peers become more central to their lives, however positive relationships with family members and carers are still essential.1

Throughout the Commissioner for Children and Young People’s many consultations, WA young people identify having a loving and supportive family as being fundamental to their wellbeing.

Communicative, warm and consistent parenting is associated with positive child and adolescent developmental outcomes.2 Increasing parent-child conflict is normal during adolescence as young people test boundaries put in place by parents. Evidence suggests that the capacity of parents to maintain connection and communication even during conflict is critical to young people feeling supported.3

In 2019, the Commissioner conducted the Speaking Out Survey which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of 4,912 Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing, including a range of questions about supportive relationships.

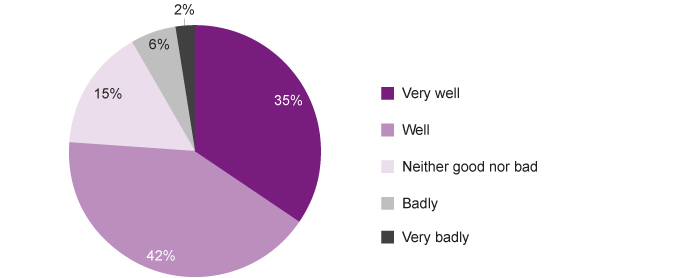

In this survey, Year 7 to Year 12 students were asked how much their mum or dad (or someone who acts as their mum or dad) cares about them. A higher proportion (82.5%) of students reported their mum (or someone who acts as their mum) cares about them a lot compared to their dad (70.0%).

Mum |

Dad |

|||||

Male |

Female |

Total |

Male |

Female |

Total |

|

A lot |

85.2 |

80.0 |

82.5 |

73.7 |

66.7 |

70.0 |

Some |

7.8 |

10.3 |

9.1 |

12.2 |

15.8 |

13.9 |

A little |

3.1 |

4.8 |

4.0 |

5.2 |

8.9 |

7.1 |

Not at all |

1.2 |

3.7 |

2.4 |

3.5 |

4.3 |

4.0 |

Does not apply to me |

2.6 |

1.2 |

1.9 |

5.3 |

4.3 |

5.1 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 students reporting that their mum or dad cares about them a lot, some, a little, not at all or it does not apply to them, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

A lower proportion of female Year 7 to Year 12 students than male students feel their mum or dad cares about them a lot (mum: 80.0% compared to 85.2%; dad: 66.7% compared to 73.7%). Additionally, a significantly lower proportion of female Year 7 to Year 12 than Year 4 to Year 6 students reported that their dad cares a lot about them (66.7% compared to 77.1%). This decrease was not found for male students.4

There were no significant differences in responses across metropolitan, regional or remote areas regarding caring parents.5

Aboriginal Year 7 to Year 12 students were significantly less likely than non-Aboriginal students to report that their mum or dad cares about them a lot (mum: 75.1% compared to 82.9%, dad: 57.8% compared to 70.7%).

Mum |

Dad |

|||

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

A lot |

75.1 |

82.9 |

57.8 |

70.7 |

Some |

13.3 |

8.9 |

13.8 |

13.9 |

A little |

4.4 |

4.0 |

8.7 |

7.0 |

Not at all |

2.5 |

2.4 |

6.9 |

3.8 |

Does not apply to me |

4.7 |

1.8 |

12.8 |

4.6 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

In contrast, Aboriginal young people in Year 7 to Year 12 were more likely than non-Aboriginal young people to report that their siblings care about them a lot (54.1% compared to 47.3%) and other family care about them a lot (60.6% compared to 54.3%).6

These results may be influenced by Aboriginal families’ more collective approach to child-rearing, where for many Aboriginal people the definition of ‘family’ is based around a kinship system which is much broader than a traditional western concept of family. Extended family members (grandparents, aunties, uncles, cousins etc.) and other community members are heavily involved in caregiving and providing support to Aboriginal parents and children.7 Thus, for many Aboriginal children and young people there are multiple adults who share the responsibility to support and take care of them.

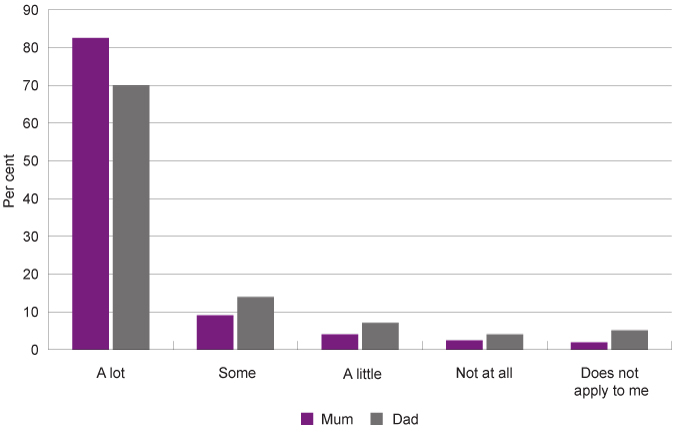

Young people's ability and willingness to talk to their parents about problems is an important indicator of a supportive and positive relationship.8

In the Speaking Out Survey, 71.1 per cent of Year 7 to Year 12 students reported that it was very much true (50.6%) or pretty much true (20.5%) that there is a parent or another adult they can talk to about their problems. Conversely, 11.0 per cent of Year 7 to Year 12 students reported that it was not at all true that there is a parent or another adult they can talk to about their problems.

There were no significant differences between regions.

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

Total |

|

Very much true |

57.5 |

44.0 |

50.4 |

51.9 |

49.8 |

50.6 |

Pretty much true |

20.7 |

20.4 |

20.7 |

18.2 |

22.3 |

20.5 |

A little true |

14.3 |

21.3 |

17.9 |

18.7 |

16.3 |

17.9 |

Not at all true |

7.4 |

14.3 |

11.0 |

11.2 |

11.6 |

11.0 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Female Year 7 to Year 12 students were significantly less likely than male students to report that it was very much true that there is a parent or another adult they can talk to about their problems (44.0% compared to 57.5%). Further, 14.3 per cent of female young people reported it was not at all true that there is a parent or another adult they can talk to about their problems (compared to 7.4% of male young people). These differences are statistically significant.

These results represent a significant decrease in the proportion of female students who report that it was very much true that there is a parent or another adult they can talk to about their problems from primary to secondary school (from 70.2% in Year 4 to Year 6 to 44.0% in Year 7 to Year 12).

A lower proportion of male students in secondary school than primary school also reported there was another parent or adult they could talk to about their problems (70.0% in Year 4 to Year 6 to 57.5% in Year 7 to Year 12), however the decrease was not as marked as for female students.

Overall, the data indicates a significant wellbeing gap between female and male students’ perceptions that widens throughout the secondary school years.

Year 4 to Year 6 |

Year 7 to Year 12 |

|||

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|

Very much true |

70.0 |

70.2 |

57.5 |

44.0 |

Pretty much true |

16.4 |

16.4 |

20.7 |

20.4 |

A little true |

9.3 |

8.2 |

14.3 |

21.3 |

Not at all true |

4.2 |

5.2 |

7.4 |

14.3 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 4 to Year 12 students reporting that it is very much true, pretty much true, a little true or not at all true that there is a parent or another adult they can talk to about their problems by year group and gender, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

With regards to having a parent or another adult they can talk to about their problems there were no significant differences between Year 7 to Year 12 students in metropolitan, regional and remote areas or Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students.

The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC)9 includes a number of questions which are related to Australian children and young people’s relationships with their parents. These include whether participants aged 10 to 15 years enjoy spending time with their parents, their closeness to their parents and who they talk to when they have a problem.10

This data shows that the majority of Australian participants aged 10 to 15 years enjoyed spending time with their parents. However, the proportion of participants who said they enjoyed spending time with their parents decreased as they got older from around 70.0 per cent at age 10 to 11 years, to just over 50.0 per cent at age 14 to 15 years.11

At 12 to 13 years of age, around 60.0 per cent of participants said that they were very close to their mother. However, by 14 to 15 years-old, 50.0 per cent of male and only 45.0 per cent of female young people said they were very close to their mother. Fewer participants felt close to their father, with 47.0 per cent of male young people aged 14 to 15 years and only 35.0 per cent of female young people saying they were very close to their father.12

At the same time, more young people enjoyed spending time with their parents than considered their relationship to be close. In particular, 53.0 per cent of female young people enjoyed spending time with their father, while only 35.0 per cent said they were close.13

Participants in the Commissioner’s Speaking Out Survey 2019 were asked how well their family gets along. Research shows that family functioning and conflict has a significant impact on children and young people’s mental wellbeing, with a stronger impact on female children and young people.14,15

Over three-quarters (76.4%) of Year 7 to Year 12 WA students report that their family gets along very well or well, while 8.3 per cent of students report their family gets along very badly or badly.

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

Total |

|

Very well |

38.8 |

30.6 |

35.0 |

33.3 |

29.6 |

34.5 |

Well |

42.8 |

41.3 |

42.0 |

38.7 |

48.1 |

41.9 |

Neither good nor bad |

11.8 |

18.7 |

15.0 |

17.2 |

16.5 |

15.4 |

Badly |

4.6 |

6.7 |

5.5 |

8.6 |

4.3 |

5.9 |

Very badly |

1.9 |

2.7 |

2.4 |

2.2 |

1.5 |

2.4 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 students reporting that their family gets along very well, well, neither good nor bad, badly or very badly, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

A significantly lower proportion of female Year 7 to Year 12 students than male students reported that their family gets along very well (30.6% compared to 38.8%).

There were no significant differences between geographic regions or between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Year 7 to Year 12 students.16

In the annual Mission Australia 2019 Youth Survey, 25,126 Australian young people aged 15 to 19 years responded to questions across a broad range of topics including education and employment, participation in community activities, general wellbeing, values and concerns and preferred sources of support.

The 2019 sample included 2,766 young people from WA.17 One-half of WA respondents (50.3%) were male and 45.8 per cent were female with remainder choosing either ‘other or ‘preferred not to say’. Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander young people comprised 5.9 per cent of WA respondents.18

Respondents to the Mission Australia survey 2019 were asked to rate how well they felt their family gets along with each other and the results are broadly consistent with the findings of the Speaking Out Survey. Among WA young people aged 15 to 19 years, 52.9 per cent rated their family’s ability in this regard as excellent or very good, while 23.3 per cent said good. Male respondents were more likely than female respondents to say that their family’s ability to get along with each other is ‘excellent’ or ‘very good’ (59.1% male compared to 47.3% female).19

Endnotes

- Yu M and Baxter J 2018, Relationships between parents and young teens, in LSAC Annual Statistical Report 2017, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Robinson E 2006, Young people and their parents: Supporting families through changes that occur in adolescence, Australian Family Relationships Clearinghouse, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Moretti MM 2004, Adolescent-parent attachment: Bonds that support healthy development, Paediatrics Child Health, Vol 9, No 8.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Lohoar S et al 2014, Strengths of Australian Aboriginal cultural practices in family life and child rearing, CFCA Paper No 25, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Yu M and Baxter J 2018, Relationships between parents and young teens, in LSAC Annual Statistical Report 2017, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 38.

- The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) follows the development of 10,000 young people and their families from all parts of Australia. The study began in 2003 with a representative sample of children (who are now teens and young adults) from urban and rural areas of all states and territories in Australia.

- Yu M and Baxter J 2018, Relationships between parents and young teens, in LSAC Annual Statistical Report 2017, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Ibid, p. 36.

- Ibid, p. 37.

- Ibid, p. 37.

- Atkinson E et al 2009, Threat is a Multidimensional Construct: Exploring the Role of Children’s Threat Appraisals in the Relationship Between Interparental Conflict and Child Adjustment, Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, Vol 37, No 2.

- Lewis A et al 2015, Gender differences in adolescent depression: Differential female susceptibility to stressors affecting family functioning, Australian Journal of Psychology, Vol 67.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, [unpublished].

- Carlisle E et al 2019, Youth Survey Report 2019, Mission Australia, p. 192. Note: Mission Australia recommend caution when interpreting and generalising the results for certain states or territories because of the small sample sizes and the imbalance between the number of young females and males participating in the survey.

- Ibid, p. 192.

- Ibid, p. 209.

Last updated December 2019

Parents who are confident and supported by family, friends and community are more likely to be able to parent effectively and consistently.

Parenting is often difficult and can be influenced by multiple factors including the health and wellbeing of the parent, the behaviour and temperament of the child, the parent’s support network and circumstances in the home environment.1 There is general agreement that parenting is now more challenging, stressful and complex than ever before.2,3

Young people aged 12 to 17 years are experiencing the various physical, cognitive and emotional changes associated with adolescence. These include striving for greater autonomy and self-reliance from parents and engaging in activities which provide them with a sense of identity separate from their family.4,5 Increasing parent-child conflict is therefore normal during adolescence as young people test parental boundaries.6

Parental confidence is important. Parental confidence or ‘parenting self-efficacy’ has been shown to be related to better outcomes for children.7 Parenting self-efficacy can be defined as a caregiver’s or parent’s confidence in their ability to successfully raise their children.8 Research shows that an individual’s belief in their ability to successfully perform a task influences their behaviour; for example, if a parent believes they are able to influence their child’s behaviour and development they are more likely to undertake activities towards that end.9,10

While parental confidence does influence competence, research has highlighted that people’s assumptions about what effective parenting involves often do not align with the views of child health and development experts.11

There is no recent data available on whether WA parents feel confident and supported in their parenting.

The following data is sourced from surveys of parent’s self-reported feelings of confidence. There are limitations with surveys of this nature, as a question about parental ‘confidence’ does not measure competency or capability at specific parenting tasks.12

In 2013, Anglicare WA conducted a survey of 810 WA parents of school-aged children and young people (Pre-primary to Year 12). One-half of respondents were from Perth, 200 from the Great Southern region and the South West, and 200 from the Kimberley and Pilbara.13

In response to the question, ‘How confident would you say you are with your parenting skills and abilities?’, 60.0 per cent of respondents answered that they were extremely confident with their parenting skills and 32.0 per cent were confident. The respondents also said that talking to their children about their needs and wants was the most influential factor in their parenting skills and abilities.14

Similarly, a 2017 survey of Victorian parents (the Parenting Today in Victoria research project) assessed parents’ perceptions of their parenting skills using the ‘Me as a parent’ scale,15 which comprised 16 questions on a five-point scale.16 This study found that a significant majority (91.0%) of parents had confidence in themselves as a parent.17 However, parents’ assessment of their self-efficacy progressively decreased as their children aged (i.e. parents of children aged 0 to two years reported higher scores than parents of young people aged to 13 to 18 years).18

These results contrast with the findings of a 2005 research project commissioned by the Australian Childhood Foundation and Monash University that surveyed 501 Australian parents (83 parents in WA). The study included parents of children from ages 0 to 18 years.19

The 2005 study found that the majority of parents (63.0%) were concerned about their level of confidence as parents. Many of the parents (38.0%) admitted that parenting did not come naturally to them.20 Parents in this study felt that they needed to ‘get parenting right’ and that this added unnecessary stress. One in five stated that they would not request help for fear of being negatively judged and criticised.21

The difference in results between these studies could be due to different methodologies, survey designs and possible changes in attitudes in the intervening years.

More recent research in WA is required to determine whether WA parents continue to feel confident in their parenting roles

Most parents find parenting demanding and stressful at times and they periodically may require resources and support.22 It is important that parents feel comfortable asking for help when they have parenting issues or concerns.

In the 2013 Anglicare parenting survey, the majority of WA parents (64.0%) said that family members and friends were a critical support mechanism. Resources such as books, classes and the internet were used by 55.0 per cent of respondents to develop their parenting skills and knowledge.23 No further breakdown by parents’ gender, region or age of children was published.

While not WA-based, the Parenting Today in Victoria survey reported that parents from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and especially those with lower educational attainment tended to be slightly more punitive in their parenting. However, for those parents experiencing disadvantage, feeling confident and effective was important, with those who were confident more likely to display positive parenting behaviours.24 This study also found that parents experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage attended Maternal and Child Health first-time parents groups less.25

In regards to Aboriginal families, Aboriginal parenting practices can differ quite significantly from those in non-Aboriginal families. One particular difference is that Aboriginal families have a collective approach to child‑rearing, where raising children is a shared responsibility within the community. The definition of ‘family’ in Aboriginal communities is based around a kinship system which is much broader than a traditional western concept of family. Extended family members (grandparents, aunties, uncles, cousins etc.) and other community members are heavily involved and provide significant support to Aboriginal parents and children.26

The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC) measured parenting efficacy using the Parent Empowerment and Efficacy Measure (PEEM) which was developed during the NSW Pathways to Prevention project.27 They concluded that for Aboriginal primary carers, resilience, satisfaction with relationships, feeling part of the community and community safety were important factors that led to them feeling more confident and effective.28

There is no data available on how confident or supported WA Aboriginal parents and carers feel about their parenting.

Endnotes

- Department of Social Services 2015, Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children—Report from Wave 5, Australian Government.

- Centre for Community Child Health 2006, Policy Brief No 1 2006: Early childhood and the life course, Royal Children’s Hospital, p. 1.

- Tucci J et al 2005, The changing face of parenting, Australian Childhood Foundation, p. 21.

- Yu M and Baxter J 2018, Relationships between parents and young teens, in LSAC Annual Statistical Report 2017, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Melbourne Children’s Research Institute 2015, Transitioning from childhood to adolescence, Commonwealth of Australia.

- Moretti MM 2004, Adolescent-parent attachment: Bonds that support healthy development, Paediatrics Child Health, Vol 9, No 8.

- Wittkowski A et al 2017, Self-Report Measures of Parental Self-Efficacy: A Systematic Review of the Current Literature, Journal of Child and Family Studies, Vol 26, No 11.

- Ibid.

- Tazouti Y and Jarlégan A 2019, The mediating effects of parental self-efficacy and parental involvement on the link between family socioeconomic status and children’s academic achievement, Journal of Family Studies, Vol 25, No 3.

- Coleman P and Karraker K 1997, Self-Efficacy and Parenting Quality: Findings and Future Applications, Developmental Review, Vol 18, p. 67.

- Volmert A et al 2016, Perceptions of Parenting: Mapping the gaps between Expert and Public Understandings of Effective Parenting in Australia, Parenting Research Centre.

- Wittkowski A et al 2017, Self-Report Measures of Parental Self-Efficacy: A Systematic Review of the Current Literature, Journal of child and family studies, Vol 26, No 11.

- Anglicare WA 2013, The Parenting Perceptions Report 2013, Anglicare WA, p. 1.

- Ibid, p. 17.

- The ‘Me as a parent’ scale is a 16-item self-report scale in an Australian context for clinical and research use. The scale measures global beliefs about self-efficacy, personal agency, self-management, and self-sufficiency, thought to constitute parent self-regulation perceptions. Source: Hamilton VE et al 2015, Development and Preliminary Validation of a Parenting Self-Regulation Scale: “Me as a Parent”, Journal of Child and Family Studies, Vol 24.

- This research was conducted by IPSOS using a random sampling methodology to ensure a representative sample was surveyed.

- Parenting Research Centre (PRC) 2017, Parenting Today in Victoria: Report of Key Findings, produced for the Victorian Department of Education and Training, PRC, p. 103.

- Parenting Research Centre (PRC) 2017, Parenting Today in Victoria: Report of Key Findings, produced for the Victorian Department of Education and Training, PRC, p. 98.

- Tucci J et al 2005, The changing face of parenting, Australian Childhood Foundation, p. 10.

- Ibid, p. 11.

- Ibid, p. 22.

- Centre for Community Child Heath 2007, Policy Brief No 9 2007: Parenting young children, Royal Children’s Hospital, p. 1

- Anglicare WA 2013, The Parenting Perceptions Report 2013, Anglicare WA, p. 17.

- Parenting Research Centre (PRC) 2018, Research Brief: Parenting with disadvantage, produced for the Victorian Department of Education and Training, PRC.

- Ibid.

- Lohoar S et al 2014, Strengths of Australian Aboriginal cultural practices in family life and child rearing, CFCA Paper No 25, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Department of Social Services (DSS) 2015, Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children—Report from Wave 5, Australian Government, p. 21.

- Ibid, p. 26.

Last updated August 2020

Relationships with friends are critical for young people aged 12 to 17 years. Adolescence is a critical period where young people are increasing their independence from their family and friendships become more important.

Friendships provide young people with social and emotional support and can be a protective factor against bullying and mental health issues.1,2,3 Supportive relationships with friends also help young people develop patterns of persistence and motivation in their schooling.4 At the same time, attitudes of friends can also have negative influences on a range of behavioural, social-emotional and school outcomes.5

The Commissioner's consultations with children and young people across WA have consistently found that having friends is one of the most important things to them.

In 2019, the Commissioner conducted the Speaking Out Survey which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of 4,912 Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing, including a range of questions about supportive relationships.

In this survey, a majority (85.2%) of students in Year 7 to Year 12 felt they had enough friends, while 14.8 per cent of students felt they did not have enough friends. A significantly lower proportion of female Year 7 to Year 12 young people than male young people felt they had enough friends (88.3% compared to 82.2%).6

Female Year 7 to Year 12 students were also significantly less likely than male students to report they are very good at making and keeping friends (46.4% compared to 55.9%). Over 10 per cent (11.2%) of female students reported being not so good at making and keeping friends (6.2% for male students).7

Participants were also asked how much their friends care about them, with 44.0 per cent of Year 7 to Year 12 students reporting their friends care about them a lot and 46.0 per cent reporting they care about them some. Almost five per cent (4.6%) reported that their friends cared about them a little.

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

Total |

|

A lot |

42.7 |

45.8 |

43.3 |

48.9 |

40.9 |

44.0 |

Some |

47.6 |

44.5 |

46.6 |

42.2 |

47.9 |

46.0 |

A little |

4.6 |

4.2 |

4.8 |

3.2 |

5.5 |

4.6 |

I don’t know |

5.1 |

5.5 |

5.3 |

5.7 |

5.7 |

5.3 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Male Year 7 to Year 12 students were somewhat less likely than female students to feel that their friends cared a lot about them (42.7% compared to 45.8%), although this difference was not significant. Responses were similar for students across geographic regions and Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students.8

Notably, 50.3 per cent of male and 61.5 per cent of female Year 7 to Year 12 students reported that friends were helpful for discussing emotional health worries, which was the most common response across a range of sources.9 For more information refer to the Mental health indicator.

Relationships with peers at school are one of the main sources of friendships for adolescents. Analysis of the results from the Speaking Out Survey show that young people with caring peer relationships have a greater sense of belonging at school and are more likely to enjoy attending school.10

According to results from the Speaking Out Survey 2019, 69.2 per cent of Year 7 to Year 12 students usually get along with their classmates, while 25.3 per cent get along with their classmates sometimes. Responses were similar for male and female Year 7 to Year 12 students and across geographic regions.

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

Total |

|

Usually |

72.3 |

66.8 |

70.2 |

66.4 |

60.8 |

69.2 |

Sometimes |

22.8 |

27.3 |

24.5 |

27.2 |

32.8 |

25.3 |

Hardly ever |

2.7 |

3.3 |

2.9 |

3.1 |

3.5 |

3.0 |

Not at all |

1.5 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

1.7 |

2.4 |

1.6 |

Prefer not to say |

0.8 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

1.5 |

N/A |

0.9 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

A lower proportion of Aboriginal than non-Aboriginal Year 7 to Year 12 students reported usually getting along with classmates (62.8% Aboriginal compared to 69.5% non-Aboriginal) and a higher proportion reported getting along hardly ever or not all (6.8% compared to 4.6%).11 These differences were notable but did not reach statistical significance.

In the Commissioner’s consultations, Aboriginal children and young people have expressed slightly different views on friendship from non-Aboriginal children and young people. While Aboriginal young people highly valued their friends, they considered their family to be the most important source of happiness, support and guidance.12

The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC)13 includes a number of questions which are related to Australian children and young people’s relationships with their peers. This study is not designed to provide jurisdictional breakdowns.

A significant majority (80.0% to 90.0%) of Australian young people aged between 12 and 15 years reported having good friends who they trusted and who they felt respected their feelings and listened to them.14

On almost all items, female young people reported higher peer attachment than male young people. For example, female respondents were far more likely to have friends who encouraged them to talk about their difficulties (70.0% of female young people compared to 45.0% of male young people).15

A high proportion of both female (86.0%) and male (82.0%) young people reported that their friendship groups displayed positive attitudes, including positive attitude towards school and academic achievement, and positive moral behaviour.16

Culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) children and young people can find it more challenging to develop supportive friendships in Australia. In 2015, the Commissioner asked almost 300 WA children and young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds (CALD) about the positive things in their lives, the challenges they face, their experiences settling in Australia and their hopes for the future. In this consultation, CALD children and young people spoke about how difficult it was to make friends in a new country, particularly when you look or act differently or have trouble understanding English. Naturally however, they saw making friends they could connect with and trust as really important.17

Adolescence for CALD young people can be particularly difficult where development of their cultural identity is important to them, however, due to discrimination and stereotypes this identity may not be viewed favourably by the wider Australian community.18 Additionally, research has highlighted that CALD young people can sometimes be restricted from making new friends or socialising with friends by their families, due to cultural differences.19

Endnotes

- Healy KL and Sanders MR 2018, Mechanisms Through Which Supportive Relationships with Parents and Peers Mitigate Victimization, Depression and Internalizing Problems in Children Bullied by Peers, Child Psychiatry and Human Development, Vol 49, No 5.

- Bayer J et al 2018, Bullying, mental health and friendship in Australian primary school children, Child and Adolescent Mental Health, Vol 23, No 4.

- Gray S et al 2018, Adolescents relationships with their peers, in LSAC Annual Statistical Report 2017, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 47.

- Martin A and Dowson M 2009, Interpersonal Relationships, Motivation, Engagement, and Achievement: Yields for Theory, Current Issues, and Educational Practice, Review of Educational Research, Vol 79 No 1, pp. 327-365.

- Gray S et al 2018, Adolescents relationships with their peers, in LSAC Annual Statistical Report 2017, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2016, Speaking out about wellbeing: Children and young people speak out about friends, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) follows the development of 10,000 young people and their families from all parts of Australia. The study began in 2003 with a representative sample of children (who are now teens and young adults) from urban and rural areas of all states and territories in Australia.

- Gray S et al 2018, Adolescents relationships with their peers, in LSAC Annual Statistical Report 2017, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 48.

- Ibid, p. 49.

- Ibid, p. 57.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2016, Children and Young People from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds Speak Out, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, p. 21.

- WA Office of Multicultural Interests 2009, Not drowning, waving: Culturally and linguistically diverse young people at risk in Western Australia, WA Government, p. 17.

- Ibid, p. 11.

Last updated August 2020

Positive relationships with other adults outside of the immediate family are important for young people’s wellbeing.1

Supportive and positive relationships with other adults should be warm, caring and respectful. They provide young people with the opportunity to tell an adult about a situation they would not like to tell their parents and ask for advice from someone with greater experience and knowledge than their friends.2

Research suggests that positive relationships with non-parental adults support young people’s wellbeing by providing them with a sense of value, purpose, identity and attachment to their community.3 Conversely, negative relationships or experiences (such as discrimination, being treated unfairly or badly) with other adults can foster a sense of worthlessness, powerlessness and negative self-concept.4

Young people who have a significant non-parental adult in their lives have also been shown to have more positive academic attitudes, motivation, school attendance and achievement, than young people without a supportive non-parental adult.5

In 2019, the Commissioner for Children and Young People (the Commissioner) conducted the Speaking Out Survey which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of 4,912 Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing, including a range of questions about supportive relationships.

Participants were asked: If you were having any serious problems, is there an adult you would feel okay talking to? It should be noted that this question did not exclude parents or carers and likely includes responses relating to talking to main caregivers.

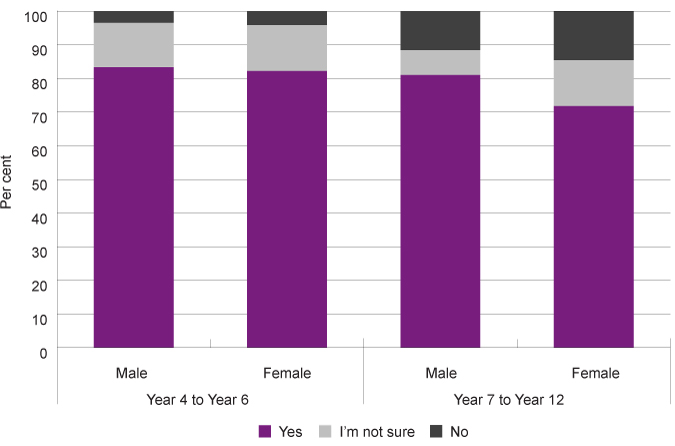

Over three-quarters (76.4%) of Year 7 to Year 12 students responded that they do have an adult they feel okay talking to, 13.2 per cent responded that they do not have an adult they feel okay talking to and 10.5 per cent were not sure.

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

Total |

|

Yes |

81.0 |

71.8 |

76.4 |

74.2 |

81.9 |

76.4 |

No |

11.6 |

14.5 |

12.8 |

16.0 |

11.1 |

13.2 |

I’m not sure |

7.4 |

13.6 |

10.8 |

9.8 |

7.0 |

10.5 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

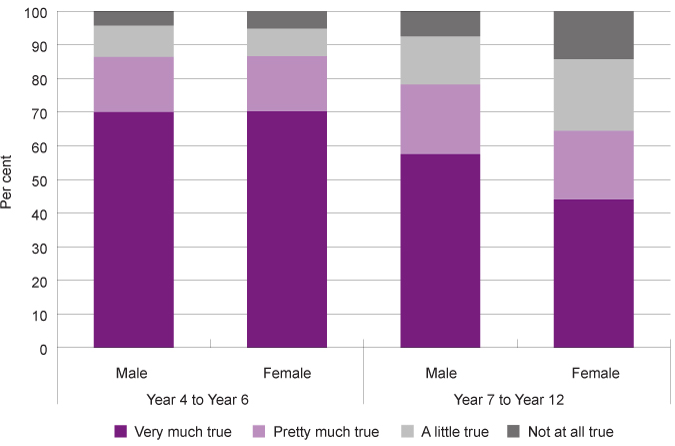

A significantly lower proportion of female students than male students reported they had an adult they would feel okay talking to (71.8% compared to 81.0%). There were no significant differences across geographical regions.

In high school there is a significant negative shift with a lower proportion of Year 7 to 12 students than Year 4 to 6 students having an adult they feel okay talking to (76.4% compared to 82.9%) and a higher proportion who do not have an adult they feel okay talking to (13.2% compared to 3.7%).

Years 4 to 6 |

Years 7 to 12 |

|||||

Male |

Female |

Total |

Male |

Female |

Total |

|

Yes |

83.3 |

82.2 |

82.9 |

81.0 |

71.8 |

76.4 |

No |

3.5 |

4.2 |

3.7 |

11.6 |

14.5 |

13.2 |

I'm not sure |

13.2 |

13.6 |

13.4 |

7.4 |

13.6 |

10.5 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Furthermore, in primary school (Year 4 to Year 6) male and female students had similar responses, however in high school, a much lower proportion of female than male students reported they had an adult they would feel okay talking to.

Proportion of students reporting they do have, do not have or don’t know whether they have an adult they feel okay talking to if they were having serious problems by year group and gender, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

This data shows a significant increase in the proportion of students who do not have an adult they feel okay talking from primary to high school for both male and female students. For female students, the proportion increases from 4.2 per cent in Years 4 to 6 to 14.5 per cent in Years 7 to 12. For male students the proportion increases from 3.5 per cent in Years 4 to 6 to 11.6 per cent in Years 7 to 12.

During adolescence, supportive relationships with non-parental adults can be in the form of mentoring relationships.6 Research from the United States using representative data from a longitudinal survey7 showed that informal adult mentors can have a significant positive influence on young people’s academic outcomes, particularly young people experiencing disadvantage.8

This research also found that young people with more resources (e.g. supportive family and friends, higher socioeconomic status and parental educational attainment) were more likely than other young people to have mentors, but young people with fewer resources were likely to benefit more from having a mentor – particularly teacher mentors.9

In the school environment, positive relationships between students and teachers can have a long-lasting impact and contribute to students’ academic and social development. They also enable students to feel safe and secure in their learning environments and promote engagement with school and learning.10,11

According to the Commissioner’s Speaking Out Survey, three-quarters (62.7%) of Year 7 to Year 12 students in WA get along with their teachers. Almost one-third (30.7%) of students get along sometimes and six per cent hardly ever or never get along with their teachers.12

In addition, a majority (61.5%) of Year 7 to Year 12 students reported that it is either very much true (24.3%) or pretty much true (37.2%) that there is a teacher or another adult at their school who really cares about them.13

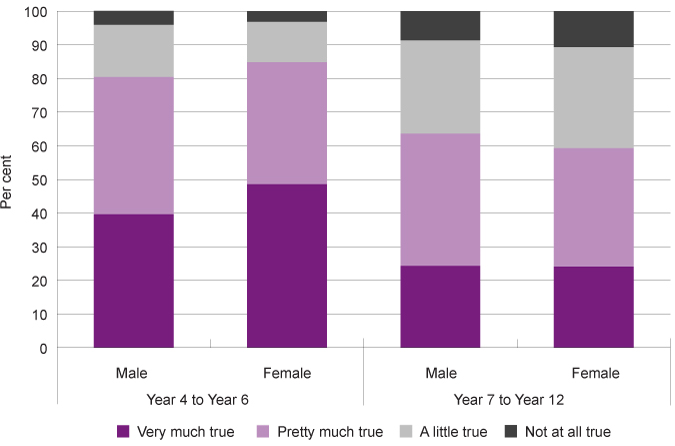

The responses from male and female students in Years 7 to 12 were largely similar, however among Year 4 to Year 6 students, female respondents were significantly more likely than male respondents to report that it was very much true that a teacher or another adult at their school really cares about them (48.6% compared to 39.6%). While the proportion of students saying it is very much true decreased for both male and female students, the proportion of female students saying this halved from primary school to high school from 48.6 per cent to 24.1 per cent.

Years 4 to 6 |

Years 7 to 12 |

|||

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|

Very much true |

39.6 |

48.6 |

24.3 |

24.1 |

Pretty much true |

40.8 |

36.2 |

39.3 |

35.2 |

A little true |

15.5 |

12.0 |

27.7 |

30.0 |

Not at all true |

4.2 |

3.2 |

8.7 |

10.7 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of students reporting it is very much true, pretty much true, a little true or not at all true that there is a teacher or another adult who really cares about them at school by year group and gender, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

For this question, a significantly higher proportion of Aboriginal than non-Aboriginal Year 4 to Year 6 students reported that it is very much true that there is a teacher or other adult at school who really cares about them (34.6% compared to 23.6%).14

For more information refer to the A sense of belonging and supportive relationships at school indicator.

Endnotes

- Goswami H 2012, Social Relationships and Children’s Subjective Well-Being, Social Indicators Research, Vol 107, No 3.

- Sterrett EM et al 2011, Supportive Non-Parental Adults and Adolescent Psychosocial Functioning: Using Social Support as a Theoretical Framework, American Journal of Community Psychology, Vol 48, No 0.

- Goswami H 2012, Social Relationships and Children’s Subjective Well-Being, Social Indicators Research, Vol 107, No 3.

- Ibid.

- Sterrett EM et al 2011, Supportive Non-Parental Adults and Adolescent Psychosocial Functioning: Using Social Support as a Theoretical Framework, American Journal of Community Psychology, Vol 48, No 0.

- A mentor can be defined as someone who takes a special interest in a young person and offers advice and support to help that young person. Source: Erickson L et al 2011, Informal Mentors and Education: Complementary or Compensatory Resources?, Sociology of Education, Vol 82, No 4.

- The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health is a multi-wave longitudinal study of adolescents in the United States.

- Erickson L et al 2011, Informal Mentors and Education: Complementary or Compensatory Resources?, Sociology of Education, Vol 82, No 4.

- Ibid.

- Berry D and O’Connor E 2010, Behavioural risk, teacher-child relationships, and social skill development across middle childhood: A child-by-environment analysis of change, Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, Vol 31, No 1, p. 1-14.

- Hamre B and Pianta R 2001, Early Teacher-Child Relationships and the Trajectory of Children’s School Outcomes through Eighth Grade, Child Development, Vol 72 No 2, p. 625-638.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

Last updated December 2019

At 30 June 2019, there were 2,420 WA young people in care aged between 10 and 17 years, more than one-half of whom (53.3%) were Aboriginal.1

There is limited information available on whether WA young people in care are supported by healthy and positive relationships. There is also limited data on whether the carers of WA children and young people in care feel confident and supported.

Positive and supportive relationships are critical for young people who are in care. Having experienced severe disadvantage and often dysfunction in their family environments, young people in care particularly need safe, positive and stable relationships that will help them lead healthy and fulfilling lives into the future.

National Standards for out-of-home care have been designed to improve the quality of care provided to children and young people in care around Australia. National Standard 11 states that children and young people in care should be supported to safely and appropriately identify and stay in touch, with at least one other person who cares about their future, who they can turn to for support and advice.2

AIHW publishes data on a set of indicators reporting against the National Standards as part of the National framework for protecting Australia's children indicators. Data for these indicators is collated by AIHW from the various Australian jurisdictions using different approaches.

To support this indicator, in 2018 AIHW presented data in The views of children and young people in out-of-home care: overview of indicator results from second national survey, 2018, collected by all Australian jurisdictions as part of their local case management processes. In total 2,428 Australian children and young people aged eight to 17 years completed the various surveys, including 643 children and young people in WA.3

WA data was collected through existing survey processes via Viewpoint, a self-assessment questionnaire. This process is not random and respondents are usually supported by a facilitator to respond to the questionnaire. Older children and young people can choose to respond independently using their own device.4

Nationally, 97.4 per cent of all survey respondents were able to nominate at least one significant adult who cared about them and who they believed they would be able to depend upon throughout their childhood.5

However, only 64.0 per cent of young people aged 15 to 17 years reported that they were getting as much help as they needed to make decisions about their future. A further 26.0 per cent reported that they were getting some help but they wanted more.6

In 2017, CREATE Foundation (CREATE) asked 1,275 Australian children and young people aged 10 to 17 years about their lives in the care system. CREATE noted in their report that the recruitment of participants proved difficult and that it resulted in a non-random sample with the possibility of bias.7

Nevertheless, 81.0 per cent of respondents indicated that they felt quite happy in their current placement; while 93.0 per cent reported feeling safe and secure.8 Respondents also said that if something worried them about their life in care they would most likely talk to their carers, followed by friends.9

This study also found that respondents found making friends relatively easy, however, those in residential care found this more difficult. Aboriginal respondents found it easier to make friends than non-Aboriginal respondents.10

Refer to the CREATE report for more detailed information on the children and young people’s relationships, including with case managers, siblings and carers.

McDowall JJ 2018, Out-of-home care in Australia: Children and young people’s views after five years of National Standards, CREATE Foundation

Wherever possible, children in care should also be supported to maintain a connection with their family. Standard nine of the National Standards is that ‘children and young people are supported to safely and appropriately maintain connection with family, be they birth parents, siblings or other family members’.11

The AIHW report: The views of children and young people in out-of-home care: overview of indicator results from second national survey, 2018 found that 9.0 per cent of 10 to 14 year-old respondents and 9.6 per cent of 15 to 17 year-old respondents reported they feel close only to their non-co-resident (biological) family. In contrast, 65.0 per cent of 10 to 14 year-olds and 57.3 per cent of 15 to 17 year-olds felt close to both their non-co-resident family and their co-resident family.12

It should be noted that ‘felt close to’ does not indicate whether the child or young person is supported to maintain contact with those family members.

The Department of Child Protection (now Department of Communities) included an indicator ‘proportion of children who have an ongoing relationship with their parents’ in the 2015–16 Outcomes Framework.13 No data was available at that time and no more recent data has been reported.

Comments from children and young people through the Department’s Viewpoint system show that many of the younger children in out-of-home care would like more information on their family, including more photos, while older children and young people would like to have greater contact with their family and be more informed about decisions affecting their lives.14

In 2016 the Commissioner asked 96 WA children and young people with experience of care about their views on raising concerns and making complaints in the care system. The consultation highlighted that having strong, stable and trusting relationships with caseworkers and carers was essential as these were the most frequently cited people children could speak to about their concerns.15 The absence of these important relationships placed children and young people at greater risk of believing they have nobody to speak to and nobody who would listen to or act on their concerns, and this led to feelings of disempowerment.16

Young people in care particularly need supportive relationships when they leave care at 18 years of age (or sometimes earlier). Many of the challenges young people face with transitioning from care are related to their lack of social or familial support.17

The Beyond 18: Longitudinal Study on Leaving Care is being conducted in Victoria and the wave two results were recently released. The study found that young people leaving care who were participating in the Beyond 18 study had generally poorer mental health, employment and education outcomes than other young people their age.18 This research also found that:

- Two thirds (66.0%) of care leavers stayed in contact with friends they had made while in care.

- Around three quarters (76.0%) of the continuing participants kept in contact with a former carer. This was less frequently an option for young people from residential care.

- Young people in residential care felt that the restrictions on spending time away from the care home, and limited opportunities for participating in after-school or community activities, could make it difficult to maintain outside social relationships.19

The Victorian survey results provide some indication on the experiences of young people in care generally and for the WA context, despite there being differences in the child protection system for each jurisdiction.

The lack of research and data reporting on the experiences and outcomes of WA young people in the care system is a significant gap.

Support for carers

Kinship, foster and other carers need to be properly supported and confident in their ability to effectively look after the young people in their care.

In 2016, the Australian Institute of Family Studies and the Department of Social Services conducted a survey of foster and kinship carers across Australia as part of the Working Together to Care for Kids Survey (WTCKS).20 In total, 175 family (kinship) and foster carers in WA participated.21

In this survey, over 90.0 per cent of carers strongly agreed or agreed that they could make a positive difference in the life of a child or young person in care. Almost two-thirds stated that they felt very well or well prepared for their caring role, indicating that over one-third did not feel well prepared.22

The majority of carers (61.0%) reported they were provided with adequate information about the child or young person’s history before they came into their care, with relative/kinship carers being more likely than foster carers to believe this was the case (69.0% compared to 52.0%). Almost one-half (46.0%) of foster carers reported they were not provided with adequate information prior to the child/young person’s arrival.23

Overall, carers perceived the services they had received to be very helpful or fairly helpful, with only a minority indicating that the services received were unhelpful. However, nearly four in ten carers said that they had some difficulty in getting the professional support they needed, with the most commonly reported barrier being long waiting lists and low support staff availability.24

Young people in care are a highly vulnerable group who need strong, positive and stable relationships to support them to have a good life. There is a critical need for more detailed and robust data about these young people’s and their carers’ experiences and opinions.

Endnotes

- Department of Communities 2019, Annual Report: 2018-19, WA Government p. 26.

- Department of Social Services 2011, An outline of National Standards for out-of-home care, Commonwealth of Australia.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2019, The views of children and young people in out-of-home care: overview of indicator results from the second national survey 2018. Cat no CWS 68, AIHW, p. 2-3.

- Ibid, p. 31.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2019, National framework for protecting Australia's children indicators: National Standards Indicator – 11.1 Significant Person, AIHW.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2019, The views of children and young people in out-of-home care: overview of indicator results from the second national survey 2018. Cat no CWS 68, AIHW, p. iv.

- McDowall JJ 2018, Out-of-home care in Australia: Children and young people’s views after five years of National Standards, CREATE Foundation, p. 17-19.

- Ibid, p. xix.

- Ibid, p. 86-87.

- Ibid, p. 73-74.

- Department of Social Services 2011, An outline of National Standards for out-of-home care, Commonwealth of Australia.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2019, The views of children and young people in out-of-home care: overview of indicator results from the second national survey 2018: Table A9.2a: Children aged 8–17 years in care who report they have an existing connection with at least one family member which they expect to maintain, Cat no CWS 68, AIHW.

- Department of Child Protection 2016, Outcomes Framework for Children in Out-of-home care in Western Australia: 2015-16 Baseline Indicator Report, WA Government.

- Department of Communities 2020, Viewpoint Reports: Western Australian – Out of Home Care January to June 2020, Department of Communities [unpublished].

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2016, Speaking Out About Raising Concerns in Care, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Ibid.

- Purtell J et al 2019, Beyond 18: The Longitudinal Study on Leaving Care Wave 2 Research Report: Transitioning to post-care life, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 27.

- Ibid, p. 2.

- Ibid, p. 5.

- Study participants were foster and relative/kinship carers who were registered as formal carers across Australia and had at least one child under 18 years of age in out-of-home care who was living with them at 31 December 2015. Qu L et al 2018, Working Together to Care for Kids: A survey of foster and relative/kinship carers. (Research Report), Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 4.

- Qu L et al 2018, Working Together to Care for Kids: A survey of foster and relative/kinship carers. (Research Report), Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 5.

- Ibid, p. viii-ix.

- Ibid, p. viii.

- Ibid, p. viii-ix.

Last updated August 2020

The Australian Bureau of Statistics Disability, Ageing and Carers, 2018 data collection reports that approximately 30,200 WA children and young people (9.2%) aged five to 14 years have reported disability.1,2

Young people with disability need positive and supportive relationships with parents and carers who feel confident in their caregiving.

In 2013, the Commissioner for Children and Young People consulted with 233 WA children with disability aged six to 18 years to find out what matters to them and how they feel about their lives. Almost all participating children and young people said that family was one of the most important things to them and supportive parents were one of the good things in their lives.3

In 2019, the Commissioner conducted the Speaking Out Survey which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing.4 This survey was conducted across mainstream schools in WA; special schools for students with disability were not included in the sample.

In this survey Year 7 to Year 12 students were asked: Do you have any long-term disability (lasting 6 months or more) (e.g. sensory impaired hearing, visual impairment, in a wheelchair, learning difficulties)? In total, 315 (11.4%) participating Year 7 to Year 12 students answered yes to this question.

A substantial proportion of students responded ‘I don’t know’ to this question and their wellbeing scores are generally less favourable than both other groups. Further analysis of these young people’s experiences will be undertaken in the future.

Due to the relatively small sample size, the following results for students who reported long-term disability are observational and not representative of the full population of students with disability in Years 7 to 12 in WA. Comparisons between participating students with and without disability are therefore not statistically significant. Nevertheless, the results provide an indication of the views and experiences of young people with disability.

All students were asked how asked how much they feel their mum or dad (or someone who acts as their mum or dad) cares about them. Young people with disability were less likely to feel that their mum or dad cares about them a lot than young people without disability.

Mum |

Dad |

|||

Young people with disability |

Young people without disability |

Young people with disability |

Young people without disability |

|

A lot |

80.5 |

84.5 |

60.9 |

72.1 |

Some |

12.6 |

7.9 |

17.0 |

13.6 |

A little |

3.2 |

3.4 |

9.9 |

6.4 |

Not at all |

2.7 |

2.3 |

6.6 |

4.6 |

Does not apply to me |

1.0 |

1.9 |

5.6 |

3.3 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Only 60.9 per cent of young people with disability felt that their dad cared about them a lot, while 16.5 per cent of young people with disability felt their dad cared about them only a little or not at all (compared to 11.0% of young people without disability).

Despite limitations with the sample size, results indicate that female young people with disability are more likely than male young people with disability to report not feeling like their dad cares about them a lot.5

Year 7 to Year 12 students with disability were less likely than students without disability to report that it was very much true that there is a parent or another adult in their home they can talk to about their problems (43.1% compared to 52.9%).6

Conversely, young people with disability were much more likely than young people without disability to report it was very much true that at school there was a teacher or another adult who really cares about them (35.6% compared to 23.7%).

Young people with disability |

Young people without disability |

|

Young people without disability |

35.6 |

23.7 |

Pretty much true |

34.6 |

38.0 |

A little true |

21.8 |

28.5 |

Not at all true |

8.0 |

9.8 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Establishing and sustaining friendships is important for all young people. Friendships promote social development and provide young people with emotional stability and enhance their resilience.7 Young people with disability have told the Commissioner that friends provide inspiration, stability, comfort, fun and acceptance.8

In the Speaking Out Survey 2019 young people with disability were less likely to feel that they had enough friends compared to young people without disability (81.5% compared to 86.0%), and more likely to find it difficult to make and keep friends (42.3% of young people with disability say they are very good at making and keeping friends compared to 53.6% of young people without disability).9

Furthermore, a greater proportion of young people with disability than without disability felt that their friends did not care about them (7.3% compared to 4.0%) or they did not know if their friends cared about them (8.0% compared to 4.6%).10

For more information on supportive relationships for young people with disability refer:

Robinson S and Truscott J 2014, Belonging and Connection of School Students with Disability – Issues Paper, Children with Disability Australia.

Being a parent or carer of a child with disability can be very challenging and stressful for a variety of reasons including, the intensity of day-to-day care routines, difficulties finding appropriate services for their child, financial stress and social isolation.11

Parents of young people with disability often have a strong belief in their child’s future with an optimistic outlook tempered with a realistic understanding of their disability, however, they find it difficult to maintain their own social life and routines.12

Parents of young people with disability (particularly mothers) have a higher risk of experiencing poor mental health.13 They will often need support from family, friends and professionals to help with their everyday caring responsibilities and also to provide them with support and respite to attend to their own mental health and wellbeing.

Australian research considering the mental health needs of mothers of children with disability, found that 75.0 per cent of mothers felt a need for support for their own mental health, yet only 58.0 per cent tried to access support. The main barriers to accessing support were that their caring duties made it difficult to schedule appointments (45.0%) and they did not think their mental health issue was serious enough to need help (36.0%).14

There is limited data about whether WA parents of young people with disability feel confident and supported in their parenting role.

Endnotes

- ABS uses the following definition of disability: ‘In the context of health experience, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICFDH) defines disability as an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions… In this survey, a person has a disability if they report they have a limitation, restriction or impairment, which has lasted, or is likely to last, for at least six months and restricts everyday activities.’ Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016, Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia, 2015, Glossary.

- Estimate is to be used with caution as it has a relative standard error of between 25 and 50 per cent. Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016, Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia, 2018: Western Australia, Table 1.1 Persons with disability, by age and sex, estimate and Table 1.3 Persons with disability, by age and sex, proportion of persons.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA (CCYP) 2013, Speaking Out About Disability: The views of Western Australian children and young people with disability, CCYP.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey: The views of WA children and young people on their wellbeing - a summary report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Morrison R and Burgman I 2016, Friendship experiences among children with disabilities who attend mainstream Australian schools, Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, Vol 76, No 3.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2013, Speaking Out About Disability: The views of Western Australian children and young people with disability, CCYP.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

- Ibid.

- Davis E and Gilson KM 2018, Paying attention to the mental health of parents of children with a disability, Australian Institute of Family Studies [website].

- Heiman T 2002, Parents of Children With Disabilities: Resilience, Coping, and Future Expectations, Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, Vol 14, No 2.

- Gilson KM et al 2018, Mental health care needs and preferences for mothers of children with a disability, Child: Care Health and Development, Vol 44, No 10.

- Ibid.

Last updated August 2020

Young people aged 12 to 17 years are experiencing the changes that the transition to adulthood brings. These include striving for greater autonomy and self-reliance, and engaging in activities which provide them with a sense of identity separate from their family.1,2

Young people can also face specific challenges associated with adolescence including mental health issues related to body image, sexual identity and self-esteem.3 In their mid to late teens, many young people start to experiment with substances and sexual activity as part of the transition to adulthood. Some young people are also at risk of disengagement from school which can lead to diminished employment prospects and adverse life outcomes including social exclusion and poverty.4,5

Strong and positive relationships are protective against a range of behaviours that can affect young people, including mental health issues, school disengagement, drug and alcohol misuse and unsafe sexual activity.6,7,8

Data from the 2019 Speaking Out Survey shows that young people experience a decline in how they rate their supportive relationships as they enter adolescence. This decline is more significant for female young people, particularly their relationships with their dad and other adults.

Overall, the Speaking Out Survey data indicates a significant gap between female and male students’ perception of their wellbeing that manifests throughout the secondary school years and can be found across multiple indicators including Mental health and feeling Safe in the home. These findings raise questions that will be subject to further analysis by the Commissioner.

Research shows that both mothers’ and fathers’ relationships with their children and their parenting styles are important for child and adolescent development.9,10 Most parents will find parenting at times demanding or stressful and will require resources and support at least occasionally.11

The support available to parents, both informal and formal, is an important factor in their capacity to parent.12 Supportive community attitudes, practical and social support from extended family, friends and community, timely information about child development and parenting issues, and access to quality programs, services and facilities are all crucial.13,14

A range of evidence-based and effective parenting programs and services are offered by government, non-government and private agencies in WA however they are not sufficiently coordinated or integrated and many are under-resourced. It is particularly critical that parents who are experiencing adversity and disadvantage are provided with access to specialised and intensive parenting support services.15

While the focus of parenting programs is often for parents with young children, parents of teenagers also require support and assistance for the various issues that arise during this period. In 2015, as part of the Our Children Can’t Wait: Review of the implementation of recommendations of the 2011 Report of the Inquiry into the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people in WA report, the Commissioner recommended better coordinated universal and targeted parenting programs and supports, including for parents of older children and young people.

Emerging research from the UK highlights that many of the most vulnerable children and young people in a community do not receive the help they need from intensive support services. Rather, the majority of children and young people who do receive intensive support services are not those in greatest need.16

However, many vulnerable children and young people receive more informal assistance and support from non-government organisations and the broader community.17 This includes neighbours, school staff and other local community members who all have a significant role in supporting vulnerable children and young people, both to mitigate the need for service intervention early on and later if children and young people fall through gaps in the service system.

Opportunities to participate in cultural and community activities that enable young people to build relationships outside of their immediate family are therefore important.

Friendships are highly influential for young people aged 12 to 17 years as during this period they are often increasing their independence from their family and turning to friends for support. Friendships provide young people with social and emotional support and can be protective against bullying and mental health issues.18,19,20

Some young people can have difficulty creating and maintaining friendships. These include young people in care, young people with disability and culturally and linguistically diverse young people. Recognising that positive and supportive friendships are critical for young people, organisations interacting with young people, including schools, should encourage programs which foster friendships.

Young people in care are a particularly vulnerable group and an important issue for these young people is whether they feel cared for and supported by the key people in their lives.21 It is well established that young people in care have a higher risk of involvement with drugs, alcohol, youth justice and long-term disadvantage over their lifetime.22 Ensuring young people in care experience safe, reliable and responsive caregiving and support is critical.23

It is also essential to ensure that young people leaving care have the support they need to successfully transition to independence.

Wherever possible, young people in care should also be supported to maintain a connection with their family. In conjunction with this, biological parents should be helped to manage any unresolved trauma and grief and address parenting issues.24

Parenting a young person with disability can be challenging. Results from the Speaking Out Survey 2019 suggest that caring and supportive relationships with parents and other adults have a significant influence on the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people, including children and young people with disability. However, research shows that parents of children and young people with disability have a higher risk of mental health issues than those with children without disability.25 High-quality programs that support parents of children and young people with disability are therefore essential.

Data gaps

Limited qualitative data exists on how WA young people experience their relationships and what influences their views.

There is limited data on whether WA parents and carers feel confident and supported in their caregiving.

The lack of research and data reporting on the experiences and outcomes of WA young people in the care system is a significant gap.

Endnotes

- Yu M and Baxter J 2018, Relationships between parents and young teens, in LSAC Annual Statistical Report 2017, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Melbourne Children’s Research Institute 2015, Transitioning from childhood to adolescence, Commonwealth of Australia.

- Ibid.

- Hancock KJ et al 2013, Student attendance and educational outcomes: Every day counts, Report for the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2015, Australia’s welfare 2015, Australia’s Welfare Series No 12, Cat No AUS 189, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

- Child Family Community Australia 2013, Family factors in early school leaving, Australian institute of Family Studies.

- Robinson E 2006, Young people and their parents: Supporting families through changes that occur in adolescence, Australian Family Relationships Clearinghouse, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Moretti MM 2004, Adolescent-parent attachment: Bonds that support healthy development, Paediatrics Child Health, Vol 9, No 8.

- Baxter J and Smart D 2010, Fathering in Australia among couple families with young children, Occasional Paper No. 37, Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, p. 15.

- Utting D 2007, Parenting and the different ways it can affect children’s lives: research evidence, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, York, England, p. 7.

- Centre for Community Child Heath 2007, Policy Brief No 9 2007: Parenting young children, Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, p. 1

- Centre for Community Child Health 2006, Policy Brief No 1 2006: Early childhood and the life course, Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, p. 1.

- Centre for Community Child Health 2004, Parenting Information Project Volume One: Main Report, Department of Family and Community Services, Canberra, p. ix.

- Anglicare WA 2013, The Parenting Perceptions Report 2013, Anglicare WA, Perth, p. 22.

- Volmert A et al 2016, Perceptions of Parenting: Mapping the gaps between expert and public understandings of effective parenting in Australia, FrameWorks Institute, p. 6.

- Little M et al 2015, Bringing Everything I Am Into One Place, Dartington Social Research Unit and Lankelly Chase, p. 50-51.

- Little M 2017, Conference paper: Relational Social Policy - Implications for Policy and Evidence, Evidence for impact: International and local perspectives on improving outcomes for children and young people, The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne.

- Healy KL and Sanders MR 2018, Mechanisms Through Which Supportive Relationships with Parents and Peers Mitigate Victimization, Depression and Internalizing Problems in Children Bullied by Peers, Child Psychiatry and Human Development, Vol 49, No 5.

- Bayer J et al 2018, Bullying, mental health and friendship in Australian primary school children, Child and Adolescent Mental Health, Vol 23, No 4.

- Gray S et al 2018, Adolescents relationships with their peers, in LSAC Annual Statistical Report 2017, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 47.

- McDowall JJ 2018, Out-of-home care in Australia: Children and young people’s views after five years of National Standards, CREATE Foundation, p. 45.

- Cameron N et al 2019, Research Briefing: Good Practice in Supporting Young People Leaving Care, Australian Childhood Foundation: Centre for Excellence in Therapeutic Care, Southern Cross University.