Mental health

Good mental health is an essential component of wellbeing and means that children and young people are more likely to have fulfilling relationships, cope with adverse circumstances and adapt to change.

Poor mental health is associated with behavioural issues, a diminished sense of self-worth and a decreased ability to cope. This has adverse effects on a child or young person’s quality of life and emotional wellbeing as well as their capacity to engage in school and other activities.1,2

Last updated July 2020

Limited data is available on whether WA children aged 6 to 11 years are mentally healthy.

Overview

This indicator reports on a number of key measures that track whether children in WA are mentally healthy. These includes the measures that consider the prevalence of mental health issues for children aged 6 to 11 years and measures that report mental health service use by children. This indicator also considers incidences of self-harm and suicide.

Key risk factors for child mental health issues include family socio-economic disadvantage, parental mental health, child temperament, bullying, experience of domestic violence, abuse, or a traumatic event.1,2,3,4

In the 2019 Speaking Out Survey, more than three-quarters (78.6%) of Year 4 to Year 6 students in WA rated their life as the best possible life.

Similar proportions of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students rated their life as the best possible life (76.9% of Aboriginal students compared to 78.7% of non-Aboriginal students).

Areas of concern

Limited data is available to assess whether mental health outcomes for WA children aged 6 to 11 years have improved as a result of any changes in mental health service provision and investment.

In 2015, children and young people in regional and remote areas of WA had a higher rate of mental disorders than children in metropolitan Perth.

From 2013 to 2017, the age-specific death rate due to suicide for Aboriginal children and young people aged five to 17 years in WA was almost 10 times higher than non-Aboriginal children and young people in WA (20.2 per 100,000 persons compared to 2.1 per 100,000 persons).5

Research shows that children in care are significantly more likely to have mental health issues than other children,6 yet there is no data publicly available on the mental health of children in care in WA or the provision of mental health services to these children.

Endnotes

- Christensen D et al 2017, Longitudinal trajectories of mental health in Australian children aged 4-5 to 14-15 years, PLoS ONE, Vol 12, No 11.

- Center on the Developing Child 2018, Toxic Stress, Harvard University [website].

- Moore S et al 2017, Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis, World Journal of Psychiatry, Vol 7, No 60.

- Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) 2015, Children's exposure to domestic and family violence: Key issues and responses: CFCA Paper No. 36 – December 2015, AIFS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2018, 3303.0 - Causes of Death, Australia, 2017, Intentional Self-Harm in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, ABS.

- Sawyer M et al 2007, The mental health and wellbeing of children and adolescents in home-based foster care, The Medical Journal of Australia, Vol 186, No 4.

Last updated July 2020

Within childhood and adolescence, higher optimism has been linked to lower rates of depression and anxiety, stronger academic achievement and higher peer acceptance.1 Research shows that an optimistic or positive outlook on life is a protective factor for mental health issues.2

A positive outlook is important for children as they develop their identity and imagine their future selves. Research suggests that having the ability to imagine a positive version of a future self is linked to better health and educational outcomes, including reduced drug use, less sexual risk taking behaviours and less involvement in violence.3

Resilience is also critical for children as it enables them to cope and thrive in the face of negative events, challenges or adversity. Key attributes of resilience in children include social competence, a sense of purpose or hope for the future, effective coping style, a sense of self-efficacy and positive self-regard.4

In 2019, the Commissioner for Children and Young People (the Commissioner) conducted the Speaking Out Survey which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of 4,912 Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing, including a range of questions about their view of themselves.5

The survey asked students to rate on a scale from 0 to 10 where they felt their life was from the worst (0) to the best (10) possible life.

Average ratings were higher for students in Years 4 to 6 than in Years 7 to 9 and 10 to 12 (7.8 in Years 4 to 6 compared to 7.1 in Years 7 to 9 and 6.5 in Years 10 to 12).6

With respect to grouped ratings (0 to 4, worst; 5 or 6; and 7 to 10, best), more than three-quarters (78.6%) of Year 4 to Year 6 students rated their life as the best possible. At the same time, 7.7 per cent of Year 4 to Year 6 students rated their life as the worst possible (rating of 0 to 4).

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

Total |

|

7 to 10 |

81.7 |

75.9 |

79.1 |

76.6 |

78.0 |

78.6 |

5 to 6 |

12.6 |

14.5 |

13.1 |

16.9 |

12.8 |

13.7 |

0 to 4 |

5.7 |

9.6 |

7.8 |

6.5 |

9.2 |

7.7 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

A significantly lower proportion of female than male Year 4 to Year 6 students rated their life as the best possible (75.9% compared to 81.7%).

Year 4 to Year 6 students in different geographic regions and Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students gave largely similar life satisfaction scores.

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Total |

|

7 to 10 |

76.9 |

78.7 |

78.6 |

5 to 6 |

15.0 |

13.6 |

13.7 |

0 to 4 |

8.1 |

7.7 |

7.7 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

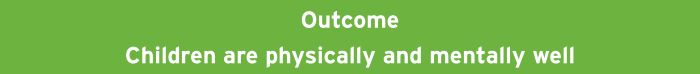

In the same survey, 89.6 per cent of Year 4 to Year 6 students strongly agreed or agreed that they feel good about themselves. Female students were less likely to strongly agree that they feel good about themselves (46.9% of female students compared to 53.6% of male students).7

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

Strongly agree |

53.6 |

46.9 |

50.3 |

50.7 |

50.8 |

50.4 |

Agree |

38.4 |

40.3 |

39.4 |

37.7 |

40.3 |

39.2 |

Disagree |

5.7 |

10.2 |

8.1 |

8.9 |

5.6 |

8.1 |

Strongly disagree |

2.2 |

2.5 |

2.1 |

2.7 |

3.3 |

2.3 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Overall, 10.4 per cent of Year 4 to Year 6 students reported that they did not feel good about themselves (8.1% disagreed, 2.3% strongly disagreed).

Highlighting differences between primary school and high school, the proportion of students reporting they felt good about themselves was significantly higher for Year 4 to Year 6 students than Year 7 to Year 12 students (89.6% Years 4 to 6 compared to 68.2% Years 7 to 12).8

A significantly lower proportion of female Year 4 to Year 6 students than male students strongly agreed that they had the ability to do things as well as others (29.0% female compared to 38.8% male).

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

Strongly agree |

38.8 |

29.0 |

34.2 |

33.8 |

31.2 |

33.9 |

Agree |

48.4 |

52.9 |

51.3 |

46.4 |

52.1 |

50.5 |

Disagree |

10.5 |

14.7 |

12.0 |

15.3 |

13.2 |

12.6 |

Strongly disagree |

2.3 |

3.4 |

2.5 |

4.5 |

3.5 |

2.9 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 4 to Year 6 students reporting they strongly agree, agree, disagree or strongly disagree that they have the ability to do things as well as others by gender, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

These results are an early indication of a wellbeing gap between female and male students that manifests more significantly throughout the secondary school years. For more information refer to the Positive outlook on life measure in the Mental health indicator for the 12 to 17 years age group.

There were no significant differences between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children’s views of themselves.

There is limited data measuring resilience in children aged 6 to 11 years. In the Commissioner’s Speaking Out Survey 2019, students in Year 7 to Year 12 were asked a series of questions about their level of resilience and how they are coping with life’s challenges. For these results refer to the Positive outlook on life measure in the Mental health indicator for the 12 to 17 years age group.

Endnotes

- Gregory T and Brinkman S 2015 Development of the Australian Student Wellbeing survey: Measuring the key aspects of social and emotional wellbeing during middle childhood, published by the Fraser Mustard Centre, Department for Education and Child Development and the Telethon Kids Institute.

- Conversano C et al 2010, Optimism and Its Impact on Mental and Physical Well-Being, Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health, Vol 6.

- Johnson SL et al 2014, Future Orientation: A Construct with Implications for Adolescent Health and Wellbeing, International Journal of Adolescent Mental Health, Vol 26, No 4.

- Cahill H et al 2014, Building Resilience in Children and Young People, A Literature Review for the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD), Youth Research Centre, Melbourne Graduate School of Education, University of Melbourne, p. 5

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey: The views of WA children and young people on their wellbeing - a summary report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Ibid, p. 39.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

- Ibid.

Last updated July 2020

Young children can, and do, experience significant mental health problems.1 Estimates suggest that approximately three-quarters of adult mental illnesses were diagnosed in adolescence and one-half were diagnosed before 15 years of age.2

Mental health3 issues in young children can be caused by multiple inter-dependent factors including a child’s genetic pre-disposition (e.g. temperament and other health issues such as intellectual disability, ADHD etc.) and their exposure to adverse experiences or environments such as poverty, family breakdown and mental health problems of a parent.4

Good mental health provides an essential foundation for children’s healthy development. Mental health issues impact children’s ability to form healthy relationships, participate in learning and cope with adversity.5 In some instances mental illness can lead to psychosocial disability where a person is unable to participate fully in life due to mental ill-health.6

Mental health issues in children under 12 years of age are often under-diagnosed. There are a number of reasons for this, including: parents under-estimating the impact and severity of mental health issues and the need for treatment, a lack of availability of specialised services, and stigma related to accessing services.7

Reliable data that provides information about the mental health and wellbeing of WA children and young people and the extent to which they experience mental health problems and disorders is limited.

The most comprehensive research on the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people in WA was the Western Australian Child Health Survey in 1995 and the Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey in 2005. These surveys found that more than one in six children aged four to 16 years had a mental health problem8 and almost one in four (24%) Aboriginal children aged four to 17 years were at high risk of clinically significant emotional or behavioural difficulties.9 These surveys have not been repeated.

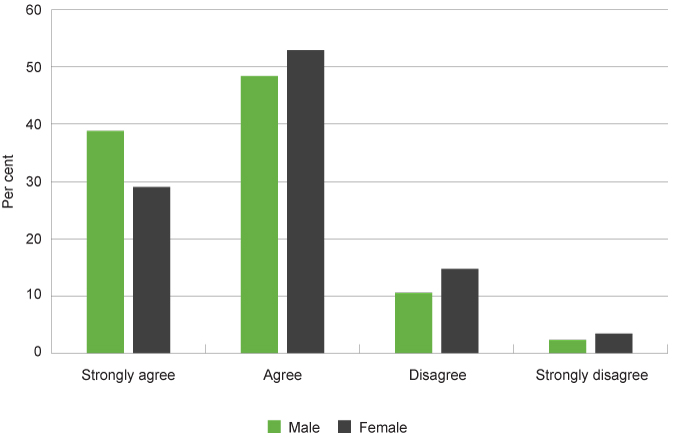

The 2015 Report on the Second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (Young Minds Matter) conducted by the Telethon Kids Institute for the Australian Government provided a comprehensive analysis of the mental health of Australian children and young people aged four to 17 years. Unfortunately, this survey could not produce estimates of mental disorders and service use at the state and territory level, or for Aboriginal children and young people.10

The Young Minds Matter survey used a number of diagnostic modules from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (DISC-IV)11 to assess mental disorders in Australian children and adolescents. Under DISC-IV, disorder status is determined according to criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Version IV (DSM_IV).12

During the survey, parents and carers completed certain modules of the DISC-IV questionnaire with a trained interviewer, older children and young people (aged 11 to 17 years) also completed a questionnaire which included the DISC-IV major depressive disorder module. For a summary of these responses refer to the Mental health indicator in the age group 12 to 17 years.

The survey estimated the 12-month prevalence of mental disorders among Australian four to 11 year-olds by gender and mental disorder category as outlined in the following table.

Male |

Female |

Total |

|

Anxiety disorders |

7.6 |

6.1 |

6.9 |

Major depressive disorders |

1.1 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) |

10.9 |

5.4 |

8.2 |

Conduct disorder |

2.5 |

1.6 |

2.0 |

Any mental disorder |

16.5 |

10.6 |

13.6 |

Source: Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing

12-month prevalence of mental disorders among children aged 4 to 11 years by gender and mental disorder category, per cent, Australia, 2015

Source: Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing

Among children aged four to 11 years, ADHD (8.2%) and anxiety disorders (6.9%) were the most common.13

There were differences between male and female children. Male children aged four to 11 years are more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD (10.9% compared to 5.4%) and anxiety disorders (7.6% to 6.1%). It should be noted that research suggests that female children are under‑diagnosed for ADHD in childhood, as the symptoms are less overt and often co-exist with different disorders from male children.14

The WA Department of Health administers WA Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System with WA parents and carers of children aged 0 to 15 years.15 In this survey they ask parents and carers about their children’s socio-emotional behaviour and mental health.

In the combined years of 2015 and 2016, WA parents and carers reported that approximately one in 24 children (4.2%) aged six to 15 years had been diagnosed with ADHD. This is similar to the proportion parents reported were diagnosed in 2009-10.16 A comparison to the Young Minds Matter survey which found that 8.2 per cent of four to 11 year olds had ADHD (determined through a DISC-IV interview) highlights that mental health issues can be under-diagnosed in children.

The following table outlines the parent and carers reports of children and young people who have ever been treated for an emotional or mental health problem.

6 to 10 years |

11 to 15 years |

|

2009–10 |

5.1 |

10.6 |

2011–12 |

6.5 |

9.7 |

2013–14 |

5.3 |

14.0 |

2015–16 |

9.9 |

12.2 |

Source: Custom report provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA from the WA Department of Health Epidemiology Branch, Selected risk factor estimates for WA children using the WA Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System, 2009–2016 [unpublished]

Based on WA parent and carer reports in 2015 and 2016, approximately 11.1 per cent of WA children aged six to 15 years had been treated for an emotional or mental health problem over their lifetime.

In the combined calendar years of 2015 and 2016, WA parents and carers reported that approximately 9.9 per cent of children aged six to 10 years and 12.2 per cent of children aged 11 to 15 years had been treated for an emotional or mental health problem in their lifetime. For six to 10 year olds, this was significantly higher than the proportion reported in the combined years of 2009 and 2010 (5.1%).

Parents and carers reported that approximately one in 10 girls and one in eight boys aged six to 15 years were treated for an emotional or mental health problem.

Female |

Male |

Total |

|

2009–10 |

6.7 |

9.1 |

8.0 |

2011–12 |

6.8 |

9.4 |

8.1 |

2013–14 |

6.9 |

13.0 |

9.9 |

2015–16 |

9.7 |

12.5 |

11.1 |

Source: Custom report provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA from the WA Department of Health Epidemiology Branch, Selected risk factor estimates for WA children using the WA Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System, 2009–2016 [unpublished]

Parents and carers were also asked whether they thought their child needed special help for an emotional, concentration or behavioural problem.

5 to 9 years |

10 to 15 years |

|

2012 |

31.5 |

29.5 |

2013 |

31.8 |

36.2 |

2014 |

32.7 |

43.7 |

2015 |

24.8* |

44.8 |

2016 |

39.2 |

37.4 |

2017 |

46.5 |

28.1 |

2018 |

33.7 |

55.0 |

Source: Patterson C et al, Health and Wellbeing of Children in Western Australia in 2018, Overview and Trends (and previous years’ reports)17

* Prevalence estimate has a relative standard error (RSE) of between 25%-50% and should be used with caution.

In 2018 the proportion of children aged five to nine years whose parents and carers felt they needed special help was 33.7 per cent. The high proportions across age groups will be in part because the term ‘special help’ is very broad and incorporates concentration and behavioural issues.

The Young Minds Matter survey highlights the difficulty of relying on parent-reported data rather than diagnostic assessment. In this survey among children meeting DSM-IV criteria for mental disorder, including clinically significant impairment of functioning, 21 per cent of parents did not identify any need for help for their child. The researchers noted this was particularly significant for the children aged four to 11 years.18

The Young Minds Matter survey also found that children and young people in low-income families, with parents and carers with lower levels of education and with higher levels of unemployment had higher rates of mental disorders. There was also a higher rate of mental disorders in non-metropolitan areas.19

Research conducted by both ReachOut Australia and Mission Australia on young people aged 15 years and over living in regional and remote Australia found that challenges associated with living in regional or remote areas included feelings of loneliness, isolation, boredom and aimlessness due to a lack of social, recreational and/or employment opportunities.20 There has been no similar research on children under 15 years of age.

Children with parents who have a mental illness also have a higher likelihood of experiencing mental health issues.21 A study in 2008 concluded that approximately 23.3 per cent of Australian children had a parent with a non-substance related mental illness.22 This can affect children in multiple ways, including experiencing a chaotic home environment, higher levels of stress and homelessness, which are all risk factors for mental health issues for the child. Protective factors, such as a supportive other parent, can buffer the effect of one parent’s mental health issues.23

Aboriginal children and young people are more likely to have mental health problems than non-Aboriginal children and young people.24 The legacy of colonisation has affected multiple generations of Aboriginal peoples.25,26 The nature of unresolved trauma and the intergenerational effects in Aboriginal communities extends ‘to all dimensions of the holistic notion of Aboriginal wellbeing, including psychological, social, spiritual and cultural aspects of life and connection to land’.27 Children and young people exposed to significant disadvantage and trauma experience far greater risk factors to their mental health – thus compounding the cycle of disadvantage.

The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey conducted in 2000 and 2001 reported that almost one quarter (24.0%) of Aboriginal children and young people aged four to 17 years were at high risk of clinically significant emotional or behavioural difficulties. This was significantly higher than the 15 per cent for WA’s general child population.28

No recent data exists on the mental health issues experienced by Aboriginal children and young people in WA.29,30

The Young Minds Matter survey could not produce estimates of mental disorders and service use for Aboriginal peoples due to the random sampling methodology and cultural issues that could not be addressed sufficiently in a national survey.31

Aboriginal adults across Australia are:

- 3 times more likely to have mental health problems managed by their general practitioner

- twice as likely to be hospitalised for mental health conditions, and

- almost twice as likely to die by suicide than non-Aboriginal Australians.32

Research strongly suggests that around half of mental health issues in adulthood develop by the mid-teens,33 therefore investment into the prevention and early intervention of mental health issues of Aboriginal children and young people should be a high priority for government.

For further information on the mental health of Aboriginal children and young people refer to the Commissioner’s 2012 policy brief: The mental health and wellbeing of children and young people: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people.

Children and young people in the youth justice system

Children and young people in the youth justice system are also more likely to have mental health issues.34 The Banksia Hill Detention Centre is the only facility in WA for the detention of children and young people 10 to 17 years of age who have been remanded or sentenced to custody. During 2017–18, approximately 148 children and young people aged between 10 and 17 years were held in the Banksia Hill Detention Centre in WA on an average day.35

In 2017, a Telethon Kids Institute research team found that 89 per cent of young people in WA’s Banksia Hill Detention Centre had at least one form of severe neurodevelopmental impairment, while 36 per cent (36 young people) were found to have Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD). While FASD is not a mental illness, it is a cognitive disability which has a significant impact on mental health and increases the likelihood of social and emotional behavioural issues that are often not diagnosed.36,37

It is of significant concern that only two of the young people with FASD had been diagnosed prior to participation in the study.38 This highlights a critical need for improved health assessment and diagnosis processes in the juvenile justice system and other services systems more broadly.

Children and young people entering youth detention have the right to be assessed to determine whether they have a physical or intellectual disability, mental health issues, learning difficulties or experience other forms of vulnerability and to have those needs met.

No other data exists on the prevalence of mental health issues for children and young people in the youth justice system in WA.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex children

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI)39 children and young people are also at an increased risk of a range of mental health problems, including depression, anxiety disorders, self-harm and suicide.40

The issues that affect LGBTI people largely stem from social and cultural beliefs and assumptions about gender and sexuality. As a result of these beliefs and social norms they have a much higher likelihood of experiencing abuse, violence and systemic discrimination at an individual, social, political and legal level than non-LGBTI people.41

Administrative data on the prevalence of self-harm behaviour for children and young people who identify as LGBTI are not available, as unlike other demographic characteristics, LGBTI status or identity is not captured in most data collections.42

Survey data has found that almost one-quarter of same-sex attracted Australians experienced a major depressive episode in 2005 and have up to 14 times higher rates of suicide attempts than their heterosexual peers.43 Furthermore, a study into the mental health of trans young people found that almost three-quarters (74.6%) of participating trans young people (aged 25 years or under) have at some point been diagnosed with depression and 72.2 per cent have been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder.44

There is no available data on the experience of mental health issues by WA children who identify as LGBTI.

For more information on LGBTI children and young people, refer to the Commissioner’s 2018 issues paper: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex (LGBTI) children and young people.

Culturally and linguistically diverse children

There is limited data on the prevalence of mental health issues for children from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds.

Data from the 2016 Census of Population and Housing shows that 17.3 per cent of 0 to 17 year-olds in WA were born in a country other than Australia and New Zealand (Oceania). The most common region of birth after Australia and New Zealand is North-West Europe (3.6%), followed by South-East Asia (2.7%) and Sub-Saharan African (1.8%).45

In WA, 17.5 per cent of people spoke a language other than English at home in 2016. Other than English, Mandarin was the most common with 1.9 per cent of WA people speaking this language at home. The next most common languages were Italian, Filipino/Tagalog and Vietnamese.46

There is some evidence to suggest that children and young people from refugee and some migrant backgrounds are more likely to experience mental health problems than the general population.47 This is often as a result of significant disadvantage and trauma related to their refugee, migration and settlement experience.48,49

Yet, research suggests that people from CALD backgrounds often do not seek help for mental health issues. This can be for cultural reasons, because information is not available in community languages, or there is no culturally appropriate service available.50

There is no available data on the experience of mental health issues by children in WA of a CALD background.

For more information refer to the Commissioner’s policy brief:

Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2013, The mental health and wellbeing of children and young people: Children and Young People from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

Endnotes

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child 2012, Establishing a Level Foundation for Life: Mental Health Begins in Early Childhood: Working Paper 6, Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University.

- Kim-Cohen J et al 2003, Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: Developmental follow-back of a prospective longitudinal cohort, Archives of General Psychiatry, Vol 60, No 7.

- The Commissioner recognises that Aboriginal people have a holistic view of mental health – a view that incorporates the physical, social, emotional and cultural wellbeing of individuals and their communities and the importance of connection to the land, culture, spirituality, ancestry, family and community. For more information refer to Dudgeon P et al (eds) 2014, Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice – Second edition, Telethon Institute for Child Health Research/Kulunga Research Network.

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child 2012, Establishing a Level Foundation for Life: Mental Health Begins in Early Childhood: Working Paper 6, Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University.

- Ibid.

- Mental Health Australia 2014, Getting the NDIS right for people with psychosocial disability, Mental Health Council of Australia.

- Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Australian Government, p. 10, 86.

- Garten A et al 1998, The Western Australian Child Health Survey: A review of what was found and what was learned, The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, Vol 15 No 1.

- Zubrick S et al 2005, The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey: The Social and Emotional Wellbeing of Aboriginal Children and Young People, Curtin University of Technology and Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, p. 25.

- Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Australian Government, p. 146.

- The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (DISC-IV) is a validated tool for identifying mental disorders in children and adolescents according to criteria specified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders Version IV (DSM-IV). Source: Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Australian Government, p. 23.

- Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Australian Government, p. 18.

- Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Australian Government.

- Quinn P 2015, Treating adolescent girls and women with ADHD: Gender-specific issues, Journal of Clinical Psychology, Vol 61, No 5.

- The WA Department of Health’s, Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System is a continuous data collection which was initiated in 2002 to monitor the health status of the general population. In 2017, 780 parents/carers of children aged 0 to 15 years were randomly sampled and completed a computer assisted telephone interview between January and December, reflecting an average participation rate of just over 90 per cent. The sample was then weighted to reflect the WA child population.

- Custom report provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA by the WA Department of Health Epidemiology Branch, Selected risk factor estimates for WA children using the WA Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System, 2009-2016 [unpublished]. Results from WA Children’s Health and Wellbeing Survey where parents and carers were asked whether a doctor had ever told them that their child has Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.

- This data has been sourced from individual annual Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System reports and therefore has not been adjusted for changes in the age and sex structure of the population across these years nor any change in the way the question was asked. No modelling or analysis has been carried out to determine if there is a trend component to the data, therefore any observations made are only descriptive and are not statistical inferences.

- Johnson S et al 2018, Mental disorders in Australian 4- to 17- year olds: Parent-reported need for help, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, Vol 52, No 2.

- Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Australian Government, p. 26.

- Ivancic L et al 2018, Lifting the weight: Understanding young people’s mental health and service needs in regional and remote Australia, ReachOut Australia and Mission Australia.

- Mowbray C et al 2006, Psychosocial outcomes for adult children of parents with severe mental illnesses: demographic and clinical history predictors, Health and Social Work, Vol 31.

- Maybery D et al 2009, Prevalence of parental mental illness in Australian families, Psychiatric Bulletin, Vol 33.

- Reupert D et al 2013, Children whose parents have a mental illness: prevalence, need and treatment, The Medical Journal of Australia, Vol 199, No 3 supplement.

- Zubrick SR et al 2005, The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey: The Social and Emotional Wellbeing of Aboriginal Children and Young People, Curtin University of Technology and Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, p. 25.

- Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission 1997, Bringing them home: Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families, Australian Government.

- Atkinson J 2013, Trauma-informed services and trauma-specific care for Indigenous Australian children: Resource sheet no 21 produced for Closing the Gap Clearinghouse, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Zubrick SR et al 2014, Chapter 6: Social Determinants of Social and Emotional Wellbeing, in Dudgeon P et al 2014, Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice, Telethon Institute for Child Health Research/Kulunga Research Network, p. 99.

- Zubrick SR et al 2005, The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey: The Social and Emotional Wellbeing of Aboriginal Children and Young People, Curtin University of Technology and Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, p. 25.

- The Young Minds Matter survey could not produce estimates of mental disorders and service use for Aboriginal peoples due to the random sampling methodology and cultural issues that could not be addressed sufficiently in a national survey (p. 146). Similarly, the ReachOut and Mission Australia survey of young people’s mental health in regional and remote areas were unable to recruit sufficient numbers of young people who identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander to be able to examine the experiences and needs of this group separately (p. 11).

- Ivancic L et al 2018, Lifting the weight: Understanding young people’s mental health and service needs in regional and remote Australia, ReachOut Australia and Mission Australia, p. 11.

- Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Australian Government, p. 146.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2015, The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2015, Cat No IHW 147, AIHW, p. 80.

- Kessler RC et al 2005, Lifetime prevalence and age of onset distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication, Archives of General Psychiatry, Vol 62, p 1.

- Justice Health & Forensic Mental Health Network and Juvenile Justice NSW 2015, 2015 Young People in Custody Health Survey: Full Report, NSW Government, p. 65.

- WA Department of Justice 2018, Annual Report: 2017–18, WA Government, p. 15.

- Brown J et al 2018, Fetal Alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD): A beginner’s guide for mental health professionals, Journal of Neurological Clinical Neuroscience, Vol 2, No 1.

- Pei J et al 2011, Mental health issues in fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, Journal Of Mental Health, Vol 20, No 5.

- Bower C et al 2018, Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and youth justice: a prevalence study amount young people sentenced to detention in Western Australia, BMJ Open, Vol 8, No 2.

- The Commissioner for Children and Young People understands there are a range of terms and definitions that people use to define their gender or sexuality. The Commissioner’s office will use the broad term LGBTI to inclusively refer to all people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex, as well as to represent other members of the community that use different terms to describe their diverse sexuality and/or gender.

- Leonard W et al 2012, Private Lives 2: The second national survey of the health and wellbeing of gay,lesbian, bisexual and transgender (GLBT) Australians, Monograph Series Number 86, The Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society, La Trobe University.

- Rosenstreich G 2013, LGBTI People Mental Health and Suicide, Revised 2nd Edition, National LGBTI Health Alliance, p. 4.

- Ombudsman WA 2014, Investigation into ways that State government departments and authorities can prevent or reduce suicide by young people, WA Government, p. 35.

- Rosenstreich G 2013, LGBTI People Mental Health and Suicide, Revised 2nd Edition, National LGBTI Health Alliance, p. 3.

- Strauss P 2017, Trans Pathways: the mental health experiences and care pathways of trans young people, Telethon Kids Institute, p. 10.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2019, Census of Population and Housing, 2016, TableBuilder – Dataset 2016 Census – Cultural Diversity, ABS.

- .id the population experts, Western Australia Community Profile – Language Spoken at Home [website], sourced from the ABS 2016 Census.

- De Anstiss H and Ziaian T 2010, Mental health help-seeking and refugee adolescents: Qualitative findings from a mixed-methods investigation, Australian Psychologist, Vol 45, No 1.

- Fazel M and Stein R 2002, The mental health of refugee children, Archives of disease in childhood, Vol 87.

- Francis S and Cornfoot S 2007, Multicultural youth in Australia: Settlement and transition, Centre for Multicultural Youth Issues for the Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth,

- Australian Department of Health, Fact Sheet 20: Suicide prevention and people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds, Australian Government.

Last updated September 2019

Despite increasing evidence that mental health problems can and do occur in young children,1 the Commissioner’s 2011 Inquiry into the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people in Western Australia and the follow up Our Children Can’t Wait report found there has been significant underfunding of mental health services for WA children and young people relative to the funding received by adult mental health services, as well as relative to need.

Providing services for mental health issues early in a child’s life not only reduces individual suffering, but can also produce long-term cost savings to the government and the community.2,3

Many children and young people with mental health issues will not access mental health services. This is for a number of reasons including stigma around seeking help, concerns about confidentiality, limited availability of affordable and age-appropriate services particularly in regional and remote locations and a low level of parental and community awareness regarding the importance of supporting children’s mental health by accessing appropriate services.4

Therefore, the administrative data in this measure will underrepresent the extent of mental health problems experienced by children in the community. However, it does provide some information on service use by WA children.

Administrative data from the WA Department of Health Hospital Morbidity Data Collection provides data on hospital separations5 for children and young people with mental health issues. It also provides information on the number of children who received services from public child and adolescent community mental health services.

Number |

Age-specific rate |

|

2012 |

112 |

8.6 |

2013 |

97 |

7.5 |

2014 |

104 |

8.1 |

2015 |

101 |

7.8 |

2016 |

107 |

8.3 |

2017 |

124 |

N/A |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Hospital Morbidity Data Collection provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

N/A - rate is not available for 2017 at time of publication.

Notes:

1. Figures only include patients who were diagnosed with ICD-10-AM Primary Diagnosis Code of Mental Health or discharged from a designated psychiatric hospital/ward.

2. Age Group is based on patient's age at the time of admission into hospital

3. Figures are subject to change.

4. Age-specific rate is the number of separations for an age group divided by the population for the age group, expressed as per 100,000 population.

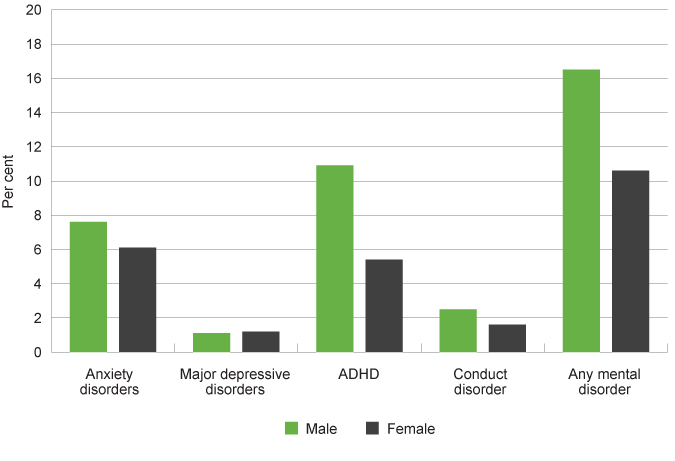

There was no increase in the age-specific rate of separations from hospital with a mental health condition for WA children aged five to 12 years of age from 2012 to 2016.

A low number of children aged five to 12 years (approximately 8 per 100,000) are hospitalised for a mental health condition. The table below highlights the increase in service-use as children age, in particular as they enter adolescence.

0 to 4 years |

5 to 12 years |

13 to 17 years |

|

2012 |

3.5 |

8.6 |

148.1 |

2013 |

4.0 |

7.5 |

142.7 |

2014 |

3.5 |

8.1 |

118.7 |

2015 |

3.7 |

7.8 |

114.0 |

2016 |

5.8 |

8.3 |

111.7 |

Total |

4.1 |

8.1 |

127.1 |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Hospital Morbidity Data Collection provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Notes:

1. Figures only include patients who were diagnosed with ICD-10-AM Primary Diagnosis Code of Mental Health (F-code) or discharged from a designated psychiatric hospital/ward.

2. Age-specific rate (ASPR) is the number of separations for an age group divided by the population for the age group, expressed as per 100,000 population.

Rates of mental-health related separations from public or private hospitals among children and young people by selected age groups, age-specific rate, WA, 2012 to 2016

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Hospital Morbidity Data Collection provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA

Rates of mental health hospital separations continue to increase until middle age, with the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reporting that the rate for overnight admitted mental health separations with specialised care is 55 per 100,000 for Australian young people under 15 years of age and 940 per 100,0000 for young people aged 15 to 24 years. In comparison, Australian adults aged 35 to 44 years have the highest rate of overnight admitted mental health separations with specialised care at 1,082 per 100,000 people.6

For the very small number of children from five to 12 years of age separating from a WA hospital with a mental health diagnosis, anorexia nervosa was the most common diagnosis (refer Healthy weight measure for a discussion). Almost four times as many children in this age group were diagnosed with anorexia than autism, which was the next most common diagnosis. Young people aged 13 to 17 years are more likely to be diagnosed with a personality disorder or depression and anorexia is the third most common disorder.7

WA children aged five to 12 years living in regional and remote areas are more likely to be discharged from a hospital with a mental health diagnosis than children living in the metropolitan area.

Metropolitan |

Non-metropolitan |

Total |

|

2012 |

64 |

48 |

112 |

2013 |

52 |

45 |

97 |

2014 |

68 |

36 |

104 |

2015 |

71 |

30 |

101 |

2016 |

71 |

36 |

107 |

2017 |

82 |

42 |

124 |

Total (2012-2017) |

326 |

319 |

645 |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Hospital Morbidity Data Collection provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Note: Figures only include patients who were diagnosed with ICD-10-AM Primary Diagnosis Code of Mental Health (F-code) or discharged from a designated psychiatric hospital/ward.

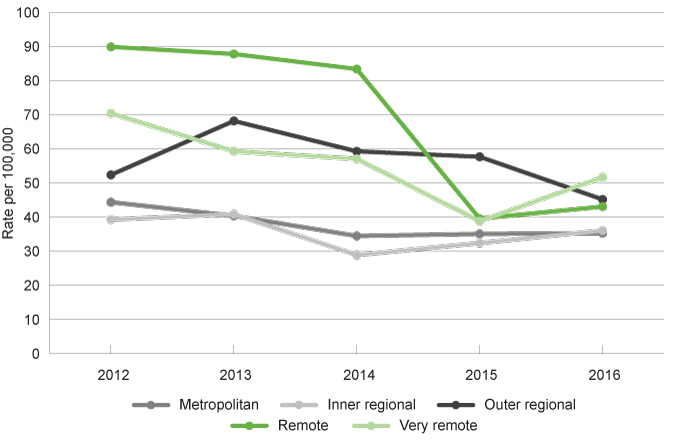

Age-specific rates for this age group by region is not available, however for children and young people aged 0 to 17 years the rate of separations from hospital is significantly higher in outer regional and remote areas than in the metropolitan area and inner regional.

Metropolitan |

Inner regional |

Outer regional |

Remote |

Very remote |

|

2012 |

44.4 |

39.3 |

52.4 |

89.9 |

70.4 |

2013 |

40.4 |

40.9 |

68.2 |

87.8 |

59.3 |

2014 |

34.5 |

28.9 |

59.3 |

83.4 |

57.1 |

2015 |

35.1 |

32.4 |

57.7 |

39.6 |

38.8 |

2016 |

35.3 |

36.1 |

45.2 |

43.1 |

51.7 |

Total |

38.0 |

35.5 |

56.6 |

68.7 |

55.4 |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Hospital Morbidity Data Collection provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Notes:

1. Figures only include patients who were diagnosed with ICD-10-AM Primary Diagnosis Code of Mental Health or discharged from a designated psychiatric hospital/ward.

2. Age-adjusted rate per 100,000 population. Direct standardisation using all age groups of 2001 Australian Standard Population in order to compare rates between population groups and different years for the same population group.

Rates of mental health related separations from public or private hospitals among children and young people aged 0 to 17 years by year and remoteness area, age-adjusted rate, WA, 2012 to 2016

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Hospital Morbidity Data Collection provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Across all regions of WA there has been a reduction in rates of mental health-related separations from 2012 to 2016.

There are multiple factors that can result in a lower rate of children and young people being discharged from hospital with a mental health diagnosis. This can include initiatives to address mental health issues earlier through community-based services, avoiding the need for a hospital stay. However, a reduction in the rate of separations, does not necessarily mean a reduction in need – it could also be a reduction in service availability.

For example, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare report on hospital resources shows that the average available number of public hospital beds per 1,000 population in WA was 2.31 in 2017–18.8 This was the lowest number of beds per 1,000 population of all states and territories (excluding the Northern Territory which did not provide the number of beds for all hospitals).

It should be noted that the Perth Children’s Hospital opened in 2018 with a mental health inpatient unit comprising a 14-bed acute section for children and adolescents who require a high level of assessment, monitoring and treatment and six beds for those who require less support and supervision during their treatment and recovery.9

WA male and female children aged five to 12 years have similar rates of separation from a hospital with a mental health diagnosis.

Male |

Female |

|||

Number |

Age-specific rate |

Number |

Age-specific rate |

|

2012 |

55 |

8.4 |

57 |

8.7 |

2013 |

50 |

7.6 |

47 |

7.2 |

2014 |

62 |

9.4 |

41 |

6.2 |

2015 |

50 |

7.6 |

51 |

7.8 |

2016 |

46 |

7.0 |

61 |

9.3 |

2017 |

57 |

N/A |

64 |

N/A |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Hospital Morbidity Data Collection provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

N/A - rate is not available for 2017 at time of publication.

* The Hospital Morbidity Data Collection does not capture data on gender but biological sex (male/female).

Notes:

1. Figures only include patients who were diagnosed with ICD-10-AM Primary Diagnosis Code of Mental Health or discharged from a designated psychiatric hospital/ward.

2. Age-specific rate (ASPR) is the number of separations for an age group divided by the population for the age group, expressed as per 100,000 population.

This changes for young people aged 13 to 17 years, with female young people in this age group being significantly more likely to separate from a hospital for mental health issues. Refer to the Mental health indicator for 12 to 17 years for more information.

The WA Department of Health also collects data on the number of WA children and young people who receive services from public child and adolescent community mental health services.

This data only includes public mental health service provision, including outpatient and community mental health services. The public mental health system typically provides services to people with moderate to severe mental health issues, whereas people with mild or emerging mental health issues are often supported by community organisations, support services or primary health providers, for example, general practitioners, counsellors, private practitioners or services such as headspace.

Number |

Age-specific rate |

|

2012 |

3,270 |

246.2 |

2013 |

3,262 |

244.5 |

2014 |

3,226 |

232.4 |

2015 |

3,229 |

228.2 |

2016 |

3,696 |

257.2 |

2017 |

4,172 |

N/A |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Mental Health Data Collection provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

N/A - rate is not available for 2017 at time of publication.

Note: Age-specific rate is the number of service contacts for an age group divided by the population for the age group, expressed as per 100,000 population.

In 2016, the age-specific rate of occasions of service increased from the previous year (257.2 per 100,000 in 2016 compared to 228.2 per 100,000 in 2015).

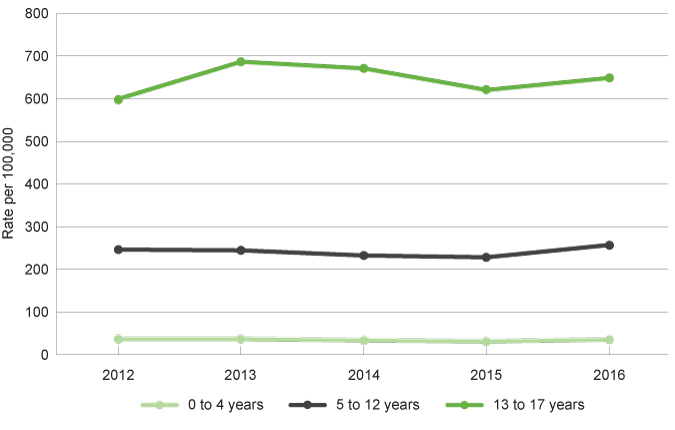

The age-specific rate of occasions of receiving public mental health services for children aged five to 12 years (257.2 per 100,000 in 2016) is significantly lower than the age-specific rate of occasions of receiving mental health services for children aged 13 to 17 years (648.7 per 100,000 in 2016). This highlights the increase in service-use as children age, in particular as they enter adolescence.

This increase could be related to higher need or severity of mental health issues as children get older and enter adolescence, particularly if their mental health issues have not been identified and addressed at an earlier stage. This could also be influenced by the lack of community awareness and identification of mental health issues in young children and also public service availability for the younger age group.

0 to 4 years |

5 to 12 years |

13 to 17 years |

|

2012 |

36.4 |

246.2 |

599.1 |

2013 |

36.4 |

244.5 |

686.5 |

2014 |

33.3 |

232.4 |

670.9 |

2015 |

30.7 |

228.2 |

620.3 |

2016 |

35.2 |

257.2 |

648.7 |

Total |

34.4 |

241.7 |

645.1 |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Mental Health Data Collection provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Note: Age-specific rate is the number of service contacts for an age group divided by the population for the age group, expressed as per 100,000 population.

Rate of service contacts at public child and adolescent community mental health services among children and young people by selected age groups, age-specific rate, WA, 2012 to 2016

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Mental Health Data Collection provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

The rate of children and young people receiving public mental health services increased from 2015 to 2016. This will continue to be monitored in future years to determine if this increase represents an ongoing trend.

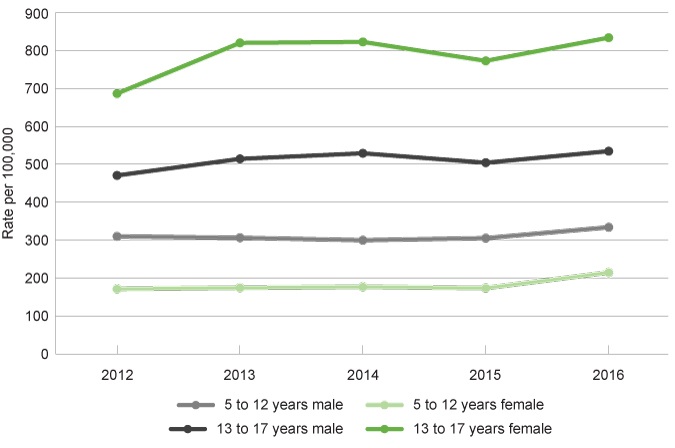

Over the five years from 2012 to 2016, male children aged five to 12 years had a significantly higher age-specific rate of contact with public mental health services (334.0 per 100,000 in 2016) than female children aged five to 12 years (214.4 per 100,000 in 2016).

Male |

Female |

|||

Number |

Age-specific rate |

Number |

Age-specific rate |

|

2012 |

2,036 |

310.0 |

1,125 |

171.3 |

2013 |

2,012 |

306.3 |

1,145 |

174.3 |

2014 |

1,970 |

299.9 |

1,161 |

176.7 |

2015 |

2,006 |

305.4 |

1,139 |

173.4 |

2016 |

2,194 |

334.0 |

1,408 |

214.4 |

2017 |

2,510 |

N/A |

1,568 |

N/A |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Mental Health Information System provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Note: Age-specific rate (ASPR) is the number of service contacts for an age group divided by the population for the age group, expressed as per 100,000 population.

N/A - rate is not available for 2017 at time of publication.

While male children have higher rates of service in the five to 12 age group, this trend is reversed in the 13 to 17 years age group where female children have a significant higher rate of receiving public mental health services (for further information refer to the Mental health indicator for 12 to 17 years).

5 to 12 years |

13 to 17 years |

|||

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|

2012 |

310.0 |

171.3 |

470.7 |

686.6 |

2013 |

306.3 |

174.3 |

514.4 |

820.2 |

2014 |

299.9 |

176.7 |

529.1 |

822.7 |

2015 |

305.4 |

173.4 |

504.3 |

772.8 |

2016 |

334.0 |

214.4 |

534.7 |

833.9 |

Total |

311.1 |

189.3 |

510.6 |

830.8 |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Mental Health Information System provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Note: Age-specific rate (ASPR) is the number of service contacts for an age group divided by the population for the age group, expressed as per 100,000 population.

Rate of service contacts at public child and adolescent community mental health services among children and young people by selected age groups and sex, age-specific rate, WA, 2012 to 2016

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Mental Health Information System provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Research suggests that there are multiple factors influencing the differences between male and female children and young people experiencing mental health issues and receiving mental health services, including:

- Male children and young people are more likely to display ‘externalising’ behaviours and problems with attention, self-regulation or antisocial behaviour, while female children and young people are ‘prone to symptoms that are directed inwardly’ or internalising behaviours, including depression, withdrawal, feelings of inferiority or shyness.10 These internalising behaviours may be less noticeable or recognisable than externalising behaviours, and therefore may not result in referral for services.

- Male young people are less likely to seek help, often due to social pressure, stigma,11 wanting to keep their problems to themselves, or feeling that they don’t have anyone to talk to.12

- Female young people are more likely to experience anxiety and depression due to social norms regarding gender roles (including body-image) and also a higher likelihood of experiencing gender-based violence and abuse.13

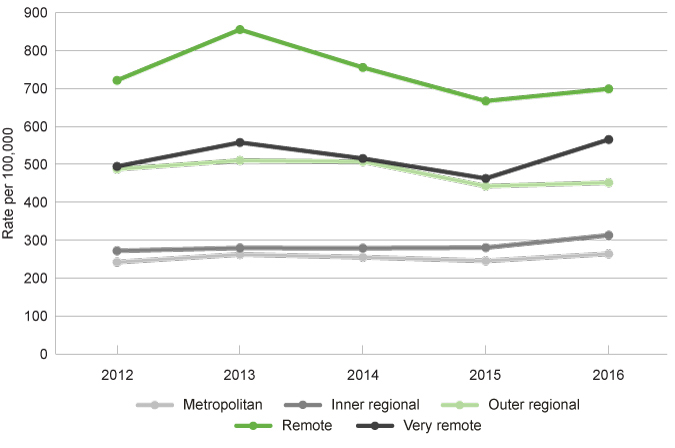

Children and young people in remote, very remote and outer regional areas have a consistently higher rate of receiving public mental health services than children and young people in the inner regional and metropolitan areas.

Metropolitan |

Inner regional |

Outer regional |

Remote |

Very remote |

|

2012 |

242.0 |

271.9 |

487.5 |

721.4 |

494.5 |

2013 |

262.2 |

279.4 |

510.3 |

855.3 |

557.6 |

2014 |

254.8 |

278.9 |

507.2 |

755.3 |

515.4 |

2015 |

245.3 |

280.3 |

442.6 |

666.9 |

462.7 |

2016 |

263.8 |

312.9 |

451.7 |

698.9 |

565.4 |

Total |

253.6 |

284.7 |

479.9 |

739.6 |

519.1 |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Mental Health Information System provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Note: Age-adjusted rate per 100,000 population. Direct standardisation using all age groups of 2001 Australian Standard Population in order to compare rates between population groups and different years for the same population group.

Rates of service contacts at public child and adolescent community mental health services among children and young people aged 0 to 17 years by year and remoteness area, age-adjusted rate, WA, 2012 to 2016

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Mental Health Information System provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

From 2013 to 2015 there was a reduction in the age-adjusted rate of children and young people receiving public mental health services in the outer regional and remote areas of WA. In 2016, the age-adjusted rate increased across all areas of WA.

Data of this nature should be considered with caution. A measure of mental health service use is not a measure of prevalence of mental health issues in a population. In particular, one child may have received multiple service contacts. Furthermore, the reasons for changes in the rate of receiving mental health services can be varied. A reduction in the rate of service could be related to issues with accessibility of the services, such that children and young people have a mental health issue but are unable to access an appropriate service in their area. Or it could be due to a lower proportion of children and young people experiencing mental health problems and a commensurate decrease in the number of services provided.

Australian research analysing Medicare data from 1 July 2007 to 30 June 2011 for mental health services found that increasing remoteness and socioeconomic disadvantage were associated with lower service activity.14

Children in remote and regional areas receive public mental health services at a higher rate than children in the metropolitan area. This is partly because there are fewer non-public mental health services or professionals available in remote and regional locations communities.15,16 However, data also suggests that children and young people in remote and regional locations have a much higher likelihood of experiencing mental health issues.17 This is for a variety of reasons including socio-economic disadvantage, isolation, greater misuse of drugs and alcohol and concerns about finding work in the future.18,19

Research suggests that even with the higher rates of receiving services in remote and regional areas there is a still a significant unmet need for children and young people in these regions.20

WA Aboriginal children aged five to 12 years are much more likely to access public mental health services than WA non-Aboriginal children aged five to 12 years (560.7 per 100,000 persons in 2016 compared to 254.7 per 100,000 persons in 2016).

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Total |

|||

Number |

Age-specific rate |

Number |

Age-specific rate |

Number |

|

2012 |

507 |

481.1 |

2,763 |

217.7 |

3,270 |

2013 |

521 |

504.0 |

2,741 |

216.0 |

3,262 |

2014 |

480 |

485.9 |

2,746 |

217.9 |

3,226 |

2015 |

482 |

493.2 |

2,747 |

221.5 |

3,229 |

2016 |

554 |

560.7 |

3,142 |

254.7 |

3,696 |

2017 |

674 |

N/A |

3,498 |

N/A |

4,172 |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Mental Health Information System provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Note: Age-specific rate (ASPR) is the number of occasions for an age group divided by the population for the age group, expressed as per 100,000 population.

N/A - rate is not available for 2017 at time of publication.

Across 2012 to 2016, Aboriginal children aged five to 12 years were 2.2 times more likely to receive public mental health services than non-Aboriginal children in this age group. In the 13 to 17 year age group Aboriginal young people were 1.9 times more likely to receive public mental health services than non-Aboriginal young people.

5 to 12 years |

13 to 17 years |

|||

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

2012 |

481.1 |

217.7 |

904.8 |

545.9 |

2013 |

504.0 |

216.0 |

1,169.4 |

613.6 |

2014 |

485.9 |

217.9 |

1,131.1 |

634.5 |

2015 |

493.2 |

221.5 |

1,199.7 |

602.5 |

2016 |

560.7 |

254.7 |

1,357.3 |

644.4 |

Total |

505.0 |

225.6 |

1,152.5 |

608.2 |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Mental Health Information System provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Note: Age-specific rate (ASPR) is the number of service contacts for an age group divided by the population for the age group, expressed as per 100,000 population.

It should be noted that this data only shows the number and rate of children and young people receiving public mental health services. It does not document the prevalence of mental health issues in these populations.

Aboriginal children and young people are more likely to be living in regional and remote areas of WA and research highlights that for many Aboriginal people (children and adults) mental health services are often not accessible, due to geographic distance and/or because they are not culturally appropriate.21,22

The 2019 WA State Coroner’s report, Inquest into the deaths of: Thirteen children and young persons in the Kimberley region, Western Australia, highlighted that most of the children and young people had previously voiced suicidal ideation or intent, but with the exception of one child, none had been directed to a primary health service or mental health service.23 In this regard, the Coroner recommended that the Department of Communities’ child protection workers and school teaching staff in the Kimberley who have regular contact with Aboriginal children receive appropriate training in suicide intervention and prevention, and that such training be provided at appropriately regular intervals (Recommendation 20).24

Children and young people in the youth justice system

Children and young people in the youth justice system are also more likely to have mental health issues.25 The Banksia Hill Detention Centre is the only facility in WA for the detention of children and young people 10 to 17 years of age who have been remanded or sentenced to custody.

In their 2017 inspection of the Banksia Hill facility, the Officer of the Inspector of Custodial Services noted that the mental health crisis care facilities were not adequate and this “created a highly inappropriate and counter-therapeutic environment to house young people who are, or had been acutely mentally unwell”.26 They also noted that, contrary to policy, less than one-third of behaviour management plans had involved consultations with a psychologist.27

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex children

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex (LGBTI) children and young people have a very high risk of mental health problems, including depression, anxiety, self-harm and suicidal thought.28

The issues that affect LGBTI people largely stem from social and cultural beliefs and assumptions about gender and sexuality. As a result of these beliefs and social norms they have a much higher likelihood of experiencing abuse, violence and systemic discrimination at an individual, social, political and legal level than non-LGBTI people.29

Administrative data on the prevalence of self-harm behaviour for children and young people who identify as LGBTI are not available, as unlike other demographic characteristics, LGBTI status or identity is not captured in most data collections.30

Research has found that LGBTI children and young people may delay seeking treatment in the expectation that they will be subject to discrimination or receive reduced quality of care.31

There is no available data on the experience of mental health issues or services received by children in WA who identify as LGBTI.

For more information refer to the Commissioner’s issues paper:

Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2019, Issues Paper: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex (LGBTI) children and young people, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

Culturally and linguistically diverse children

There is very limited information on the prevalence of mental health issues for children from a culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds. However, there is evidence to suggest that children and young people from refugee and some migrant backgrounds are more likely to experience mental health problems than the general population.32

Data and research also suggests that people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds often do not seek help for mental health issues. The Australian Bureau of Statistics reports that while eight per cent of people born in Australia who speak English at home accessed mental health related services in 2011, only 5.6 per cent of people who were born overseas and speak a language other than English at home accessed these services.33

Research has found the lack of service use can be for cultural reasons, because information is not available in community languages, or there is no culturally appropriate service available.34

There is no available data on the experience of mental health issues or services received by children and young people in WA of a CALD background.

For more information refer to the Commissioner’s policy brief:

Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2013, The mental health and wellbeing of children and young people: Children and Young People from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

Endnotes

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child 2012, Establishing a Level Foundation for Life: Mental Health Begins in Early Childhood: Working Paper 6, Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University.

- Access Economics 2009, The economic impact of youth mental illness and the cost effectiveness of early intervention, p. iii-iv.

- British Medical Association (BMA) 2017, Exploring the cost effectiveness of early intervention and prevention, BMA, p. 7.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2015, Our Children Can’t Wait – Review of the implementation of recommendations of the 2011 Report of the Inquiry into the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people in WA, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Hospital separation means the process by which an admitted patient completes an episode of care either by being discharged, dying, transferring to another hospital or changing type of care. Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2017, Admitted patient care 2015–16: Australian hospital statistics, Health services series no 75, Cat no HSE 185, AIHW p. 282.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2019, Mental Health Services in Australia – Data table for overnight admitted mental health related care, AIHW.

- Custom report provided by the Department of Health to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA on the top diagnoses of children and young people separating from a WA public or private hospital with a mental health diagnosis or discharged from a mental health inpatient unit.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2019, Hospital resources 2017–18: Australian hospital statistics: Table 4.9: Average available beds(a) and beds per 1,000 population, public hospitals, states and territories, 2013–14 to 2017–18, Health services series No 78 Cat No HSE 190, AIHW.

- WA Department of Health 2019, Perth Children’s Hospital Mental Health, WA Government.

- World Health Organisations (WHO) 2002, Gender and Mental Health, WHO.

- Chandra et al 2006, Stigma starts early: Gender differences in teen willingness to use mental health services, Journal of Adolescent Health, Vol 38.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2010, Speaking out about wellbeing: The views of Western Australian children and young people, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, p. 22

- World Health Organisations (WHO) 2002, Gender and Mental Health, WHO.

- Meadows et al 2014, Better access to mental health care and the failure of the Medicare principle of universality, Medical Journal of Australia, Vol 202, No 4.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2018, Mental Health Services in Australia: Mental Health Workforce, AIHW.

- Rural Doctors Association of Australia (RDAA) 2018, Submission to the Senate Community Affairs References Committee Inquiry into the Accessibility and quality of mental health services in rural and remote Australia, RDAA.

- Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, Department of Health, p. 28

- Enticott J et al 2016, Mental disorders and distress: Associations with demographics, remoteness and socioeconomic deprivation of area of residence across Australia, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, Vol 50 No 12.

- Ivancic L et al 2018, Lifting the weight: Understanding young people’s mental health and service needs in regional and remote Australia, ReachOut Australia and Mission Australia.

- Ibid, p. 39.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2015, Our Children Can’t Wait – Review of the implementation of recommendations of the 2011 Report of the Inquiry into the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people in WA, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, p. 35.

- Walker R et al 2014, Cultural Competence –Transforming Policy, Services, Programs and Practice in Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice, Dudgeon P et al (Ed), Telethon Institute for Child Health Research/Kulunga Research Network, p. 200.

- WA State Coroner 2019, Inquest into the deaths of: Thirteen children and young persons in the Kimberley region, Western Australia, WA Government, p. 8.

- Ibid, p. 319.

- Justice Health & Forensic Mental Health Network and Juvenile Justice NSW 2015, 2015 Young People in Custody Health Survey: Full Report, NSW Government, p. 65.

- Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services 2018, 2017 Inspection of Banksia Hill Detention Centre, WA Government, p. 53.

- Ibid, p. 41.

- Morris S 2016, Snapshot of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Statistics for LGBTI People and Communities, National LGBTI Health Alliance.

- Rosenstreich G 2013, LGBTI People Mental Health and Suicide, Revised 2nd Edition, National LGBTI Health Alliance, p. 4.

- Ombudsman WA 2014, Investigation into ways that State government departments and authorities can prevent or reduce suicide by young people, WA Government, p. 35.

- Leonard W et al 2012, Private Lives 2: The second national survey of the health and wellbeing of gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender (GLBT) Australians, Monograph Series Number 86, The Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society, La Trobe University.

- De Anstiss H and Ziaian T 2010, Mental health help-seeking and refugee adolescents: Qualitative findings from a mixed-methods investigation, Australian Psychologist, Vol 45, No 1.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2016, 4329.0.00.001 - Cultural and Linguistic Characteristics of People Using Mental Health Services and Prescription Medications: 2011, ABS.

- Australian Department of Health, Fact Sheet 20: Suicide prevention and people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds, Australian Government.

Last updated July 2020

The content for this measure considers rates of suicide and self-harm in children which can be distressing. If you or anyone you know needs urgent help please contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or the Kids Helpline on 1800 55 1800. Support is also available through headspace and beyondblue.

Intentional self-harm refers to the deliberate infliction of injury or harm on the body. In the majority of cases, it is not intended to be fatal and is not an attempt at suicide.1 Data and research shows that the age of onset of self-harm in children and young people is usually between 11 and 15 years, while for suicidal behaviour it is between 15 and 17 years.2

There is limited data on intentional self-harm for children under 12 years of age.

While children under 12 years of age do intentionally harm themselves, self-harm in young children can be subject to misinterpretation as it is difficult to assign intent.3

Children and young people may self-harm for a number of reasons including experiences of depressive and/or anxiety disorders, a crisis or difficult life event (e.g. the death of a loved one) and experiences of trauma and abuse.4 The most common methods of self-harm for young people is cutting followed by preventing wounds from healing, head-banging and poisoning.5

Most children and young people who engage in self-harming behaviours hide their injuries, therefore estimates of prevalence are problematic.6 Administrative data collected on self-harm generally reports on the number of people who were admitted to hospital as a result of injury due to intentional self-harm. Research indicates that the vast majority of children and young people who self-harm do not present for hospital treatment,7 therefore the data in this measure will underrepresent the actual number of children and young people intentionally self-harming.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare published Trends in hospitalised injury, Australia 2007–08 to 2016–17 in 2019, , which includes information on patients who were admitted to hospital as a result of injury due to intentional self-harm. They report that in 2016–17, the age-specific rate of hospitalisations due to intentional self-harm for Australian children aged 0 to 14 years was 27.4 (per 100,000).8 This increases to 426.5 per 100,000 for young people aged 15 to 19 years.9

In contrast, the Young Minds Matter survey (2015) found that around one in 10 (10,000 per 100,000) young people aged 12 to 17 years reported having ever self-harmed.10 This much higher rate of self-harm reflects the proportion of young people self-harming without necessarily attending hospital. The Young Minds Matter survey also found that only 57.6 per cent of young people who had self-harmed more than four times at any time in the past had used services for emotional or behavioural problems in the previous 12 months.11 While this data is not specific to children aged 6 to 11 years, it highlights that most children and young people who self-harm do not attend hospital.

No data is publicly available on the proportion of WA children aged 6 to 11 years who were hospitalised due to intentional self-harm.

The WA Department of Health has provided the Commissioner for Children and Young People with custom reports on rates of self-harm for WA young people aged 12 to 17 years. This data is discussed in detail in the Mental health indicator for 12 to 17 years.